NONFICTION  |

MAY 2007 – NO. 15

|

Bringing Cemeteries to Life

by A. M. Whittaker

To tour burial grounds on Memorial Day is to remember the plots

Prologue:

One wouldn't normally pass the bronze effigy that marks the final resting place of Lt. John Rogers Meigs [1] on the Arlington Cemetery tram tour. It's across from where one would ascend the tram at Arlington House, tucked away in the midst of Section 1, close to Gen. Abner Doubleday and other Civil War luminaries.

No, a proper visit to Washington, D.C.'s Arlington National Cemetery should require a comfortable pair of walking shoes, a knowledgeable and engaging tour guide, and at least three hours.

There are so many stories, and the dead demand proper respect and recognition; one shouldn't glide through it.

Background:

New York City

My introduction to cemeteries was a frightening one: from the vantage point of a five-year-old passenger in the backseat of my future step-father's car. I think the fifth year of life is the age when children truly start to comprehend the concept of death and their own mortality. I was no exception.

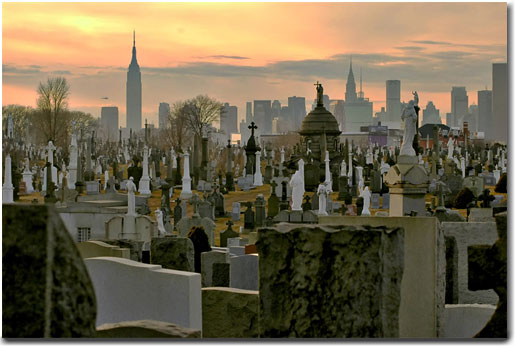

Several great necropolises rest along and beneath the Long Island Expressway (LIE) and Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE), and they mirror the sooty congestion of city blocks. Their ornate monuments actually compete with the skyline of Manhattan (see photo above). I used to ponder the people and families connected to these markers, memorials, and mausoleums. Who were they and did anyone remember or visit them in these forbidding places? There was a sense of cruel exile and abandonment.

These implanted, permanent New Yorkers also remain eternally segregated according to religion and race; to each, his own; Jewish cemeteries on one side, and Protestant and Catholic on the other. Christian cemeteries further sectioned off remote areas for African Americans and even maintained separate sets of interment records. These vast tracts are divided from one another by thick stone walls and rusted iron fences.

On the BQE, one reaches the pinnacle of the highway at the Kosciuszko Bridge [2], which affords a panoramic view of the bleak and almost endless landscape of the dead, interspersed amongst dilapidated factory buildings and smokestacks. Such a sight! It's hard to imagine that this area was once lushly forested and that these cemeteries were considered an improvement over the ones in Manhattan!

One passes through and over these cemeteries before stopping to pay the entrance toll for the Queens Midtown Tunnel — a task that, later on in life, reminded me of paying Charon to cross the Styx. Heaven was the light emerging from Manhattan at the end of the tunnel. Immediately thereafter, there was life and a sigh of relief. I hated going back in the opposite direction, even if it was to return home.

But the alternate route back home was the Queensborough/59th Street Bridge (of Simon and Garfunkel fame) and Queens Boulevard, which took us beside the Calvary Catholic Cemeteries, rising above the cars with cobblestone retaining walls supporting green mounds topped by angels and crucifixes. One could literally be buried in traffic!

Virginia

It wasn't until I first stayed with my father's family in Virginia that I discovered what a lovely and illuminating place a cemetery could be. Considerate relatives who acted as guides and teachers helped me realize that a cemetery was a tangible family tree, a time capsule, and a history book in marble, granite, slate, and sandstone; each marker became a chapter and perhaps a piece of a puzzle. They brought the cemeteries to life!

My fears concerning death subsided.

Perhaps it's a Southern thing, bringing children to cemeteries to discover and explore their roots. It's looked upon as a pleasant outing for a fine day!

My first outing was an intergenerational affair with venerable and affable cousins relating stories peppered with humorous anecdotes about family members who had "passed." My parents were divorced and it was deemed the responsibility of my father's family to fully bring me into the fold and get me up to speed with his side of the family. Virginians are passionate genealogists and take pride in rattling off the precise connections between family members. (I know what a double first cousin is and am able to explain once-removed!) Relationships among family members became clearer after this first visit. The deeply personal ways my cousins described their loved ones — our shared ancestors, family contributions to this nation, their many, expressive gravestones — was not only was enlightening, but it served to crystallize my place and purpose in the context of the family.

Considering that several of these cousins were over 80 and 90 years old in the early 1960s, it is not inconceivable that first-hand stories could span over 150 years. Indeed, many of my raconteurs were Spanish American War and WWI veterans; their own fathers were Mexican War and Civil War veterans! One cousin had escorted Teddy Roosevelt to the podium for the President's address to his West Point graduating class!

I will speak first of our ancestors, for it is right and seemly that now, when we are lamenting the dead, a tribute should be paid to their memory. There has never been a time when they did not inhabit this land, which by their valor they will have handed down from generation to generation, and we have received from them a free state.

— Pericles: Funeral Oration

As a result, this native-born Yankee expects to be permanently transplanted near her father in one of our family cemeteries near Hague, Virginia. I'll be in the shadow of an obelisk marking a Confederate General who also served in the U.S. Congress both before and after "The Wahr." There is something comforting about knowing where one's final resting place will be. This may be apocryphal, but it has been said that several Southern marriage proposals begin with, "Would you like to be buried with my people?" I'm apt to believe that.

Two of our three local family cemeteries are beautifully maintained and would be attractive to a prospective spouse, but regrettably, the third is ignominiously overrun by a jungle of locust trees, poison ivy, honeysuckle, and kudzu; its monuments are broken, sunken, askew, or lost. The cemetery itself is half buried, and the inhabitants practically forgotten. This is a shameful state of affairs but I don't have the power to correct this. Unfortunately, as our family members dwindle, so do the memories of these neglected antecedents and the exact locations of their plots. Even in our well-maintained and documented cemeteries there are sections where the markers (many them were temporary to begin with) are gone, so we have no idea who is buried there or even where they are within the boundaries of the cemetery. It has been impossible to consult any records, since there are none extant; so many were lost as a result of war and fire.

The Civil War and Arlington National Cemetery:

I'm sure President Lincoln was also aware of the decay of cemeteries during his lifetime. Those whose families could not afford expensive stones risked having their wooden markers rot and disappear. As people moved westward they abandoned their cemeteries, and many of the trails they traversed still contain many unmarked graves. Churches and churchyards were engulfed and devoured by the encroachment of the growing towns and cities. Some were vandalized.

The horrific number of dead soldiers, many of them unknown, required vast amounts of land to be acquired in order to accommodate them. Interring the remains honorably and marking the graves permanently, as well as accurately as possible, was a priority for the President during the War Between the States. After all, these soldiers had died in defense of the Union and should be treated accordingly. Notice, I wrote "Union."

This passage from the President's brief remarks at the dedication of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg sums up his view:

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate — we cannot consecrate — we cannot hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our power to add or detract.

Yes, a cemetery is a holy place.

President Lincoln relied upon his Quartermaster, General, Montgomery C. Meigs, for a solution.

General Meigs and his son, John

General Meigs's decision to confiscate the rebellious Lee family's property at Arlington plantation — directly across the Potomac River from the White House — has been attributed to revenge. Col. R.E. Lee USA, was seen as a traitor to the Union, and despite the fact that Lee himself did not own the property, it was punishment for his entire family's primary loyalty to Virginia and the Confederate cause. Ostensibly, the subsequent justification of the property's confiscation by the government was unpaid property taxes, though the family's repeated attempts to pay had been repeatedly rejected by government agents before the Lee women were compelled to move.

Meigs was a Son of the South but viewed the conflict differently from Lee; he was a fervent Unionist who detested the Confederacy and held General Lee in contempt.

As a result of General Meigs's recommendation, Arlington National Cemetery was created in 1864 as a cemetery, military post, and freedmen's village. By his direction, the first 26 graves were placed around the perimeter of Mrs. Lee's prized rose garden.

But later that year, the war became more personal to him; his son, John Rogers Meigs was killed at Swift Run Gap, VA (near Harrison in the Shenandoah) under disputed circumstances. Lt. Meigs had graduated from West Point, first in his class, less than two years before; he was 23 years old.

He was found lying in the road, service revolver at his side, and surrounded by the imprints of horses' hooves, indicating that he had been trampled after death. Gen. Meigs was not only heartbroken but incensed that his son, who was an officer, was so abused; it was intolerable. Unable to reconcile his son's death to the context of a casualty of war, he hired private investigators to hunt down the murderers. In reality, there were over 12,000 Union lieutenants amongst the over 600,000 men who lost their lives, in one way or another, during the course of the Civil War; Gen. Meigs was not the only parent who had lost a child to war.

But he was a powerful parent and eventually, General Meigs had his son's remains transferred to Arlington and ordered a bronze effigy to remind people of his son's inglorious end at the hand of the rebels; the hoof prints can be seen beside the lifeless body. The continued hatred he harbored for Robert E. Lee was boundless.

Lt. Meigs, on the other hand, rests in the shadow of his parents' sarcophagus along with his illustrious Rogers ancestors in a peaceful, grassy, and wooded area.

Epilogue:

Because I have never forgotten my initial fear of cemeteries, I endeavor to make my students' first experience a pleasant and meaningful one. There is beauty, history, and great humanity to be found in all of these places.

But Lt. Meigs's effigy has become the most important teaching moment for me while I am conducting student groups through Arlington National Cemetery. The poignant nature of the circumstances surrounding his death, and his father's connection to Arlington and Robert E. Lee, brings a very human element to the cemetery. The thousands of uniform, white stones in endless rows; the impressive monuments; the imposing historic mansion; the dignified Changing of the Guard at the Tomb of the Unknowns; the simplicity of the Kennedy graves — these things cannot match the unexpected impact of this tribute to a beloved, fallen son. Young Lt. Meigs helps put everything into perspective for students. His grave is where I am part of the most profound student discussions of the entire educational program.

As a result, I start my tour of Arlington counter-clockwise, crossing in front of the Women in Military Service Memorial, so we can visit Arlington House and Lt. Meigs first. It is my prelude to the rest of the cemetery, although we also pass Medgar Evers, Gen. Omar Bradley, President Taft, and Robert Todd Lincoln to get there.

The addition of poetry (Bivouac of the Dead, In Flanders Field, and High Flight), as well as stories of heroism — i.e. John Lincoln Clem and Audie Murphy, the examination of virtues i.e. service and sacrifice — round out the program, bringing this cemetery to life.

And rather than as casual visitors or tourists, we bond and become members of a greater, national family, to pay our respects.

No, you can't get that from a tram tour.

Postscript:

Because national cemeteries were created for the Union dead, countless Southern widows and mothers, realizing that their cemeteries would neither be maintained nor respected by the victors, introduced a movement to honor the fallen Confederates by annually refreshing cemeteries and placing flowers on each grave of their glorious dead. Originally referred to as "Decoration Day," we now observe it as "Memorial Day," extending it to all our war dead. It is a time when Americans are invited into cemeteries to acknowledge the sacrifices made on our behalf.

Memorial Day has become the time for my familiy's yearly pilgrimage. Arlington National Cemetery is my family's fourth family cemetery; my grandfather, who died nearly 20 years before I was born, is buried in the Spanish American War section. Since I do not have my own children, I continue the family tradition by relating stories to my nephew of relatives whom I knew, and whom have since passed. (It should be pointed out that my brother did not have children either, so our family name dies with us.)

Recently, I have come to terms with those vast necropolises of Brooklyn and Queens; after my first visit to them, I became mesmerized. They contain not only American history, but social context, art history, and, in some cases, even humor. But there they are, since I first saw them, stark and solid against the sky.

And these sepulchral stones, so old and brown,

That pave with level flags their burial-place,

Seem like the tablets of the Law, thrown down

And broken by Moses at the mountain's base

— Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Jewish Cemetery at Newport

One day I hope to find a tour guide who knows Hebrew and can decipher the headstones and monuments of the great Jewish ghettos of the dead. I will bring as many of my own stones as I can carry and mark these forlorn places as having been visited by the living, according to Jewish tradition. This would bring me closer to my mother's side; most of her cousins and ancestors were victims of various pogroms and the Holocaust; there are no cemeteries for them.

This past April, 72 eighth graders from Rosemont Middle School of La Crescenta, CA, visited Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester to pay tribute to two great Americans by laying wreaths at the graves of Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass. While it was extremely cold and started to sleet, the students stood respectfully while they listened to the stories told by Dr. David Anderson, an expert on Frederick Douglas, and Mrs. Joan Hunt, President of the Friends of Mount Hope Cemetery. It was pointed out that we were the first student group from the West Coast to make this pilgrimage, and perhaps the first to lay wreaths.

In California, cemeteries are streamlined lawns; stones above ground have been outlawed; the students were intrigued by the various sizes, shapes, and inscriptions of the grave markers. As they walked to and from the gravesites, many of them singled out particular stones, discussing them with their friends. I noticed a lot of finger-pointing and photos-taking.

When we were reboarding our bus, one student turned to me and said, "Whoa! This is so awesome! I wish we had more time to visit."

So did I.

Back to Top

AUTHOR BIO:

A. M. Whittaker is a professional educational program planner and itinerary designer for curriculum-based tours throughout the United States and Canada. She is a native New Yorker who currently lives in Alexandria, VA.

LOST RSS Feed

LOST RSS Feed

LOST RSS Feed

LOST RSS Feed