LOST PLACE  |

APRIL 2007 – NO. 14

|

323 Prospect Place

by Josh Jackson

A Brooklyn building still sits at the side of a phantom road

Last fall, I was walking through Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, when a residence caught my eye. The building was a fairly standard one — a classic three-story brownstone built, in this case, from brick. Rather, what caught my eye was its position: it was rotated about 60 degrees from the rest of the street grid.

323 Prospect Place

Photo Credit

Buildings don't build themselves, and whoever built this one located it the way they did for a reason. Especially in brownstone Brooklyn, where row houses are the dominant architectural feature, buildings usually face the street.

In this case, either someone decided to build it differently or the street it once faced no longer existed.

Corner of Prospect Place and Underhill Avenue

Photo Credit

Stepping back, I noticed that the building next door, which appeared to have been built more recently, was angled like its neighbor despite a corner that fit the existing street layout. Moreover, a new building under construction was also similarly rotated — clearly the plots of land in this area were oriented towards some lost feature of the urban landscape.

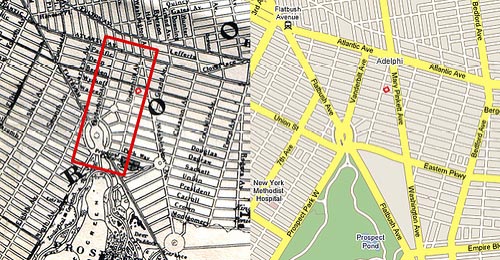

323 Prospect Place in the red box. Viewed from above, it seems that a whole block has been dropped from a different street grid into that of Prospect Heights. Why?

Photo Credit

One of my first theories was inspired by the High Line, an abandoned freight line on Manhattan's West Side. At the turn of the century, the Vanderbilt railyard (now better known as the Atlantic Yards) was ringed by Brooklyn's meatpacking industry. To facilitate the movement and loading of freight, the Armour Packing company built an elevated freight line to cross Atlantic Avenue.

Atlantic Avenue looking west towards 5th Avenue, circa 1908. From Arrt's Arrchives.

Perhaps, I imagined, the freight line cut southeast through Prospect Heights to the rotated block. There was once a dye factory on the block, built in 1912 by Dr. William Gerald Beckers. The factory was located at 107-113 Underhill Avenue, literally around the corner from 323 Prospect Place. Maybe the freight line served this factory, its structure creating the angled building footprints. Indeed, a 1914 explosion wrecked the plant: could the explosion have destroyed the elevated freight line too, eliminating the structure that caused the buildings' unusual orientation?

Sadly, there is no evidence of this whatsoever — my best guess now is that the elevated line ended not far from where it started: near the yards. For a time, I gave up on explaining the unusual placement of the 323 Prospect Place. Then, after a hiatus of several months, I found myself poking around old maps of Brooklyn again, and this time I saw something I hadn't noticed before.

Left: 1866 Johnson's Map (Photo Credit). Right: 2007 Google Map.

On an 1866 map, there was a street that doesn't exist today. Most likely, the street didn't exist yet in 1866 either, but the fact that it was mapped gave me an idea. I realized that the area was probably redesigned by Olmstead and Vaux as they planned Prospect Park and Grand Army Plaza — perhaps this would explain the placement of 323 Prospect Place.

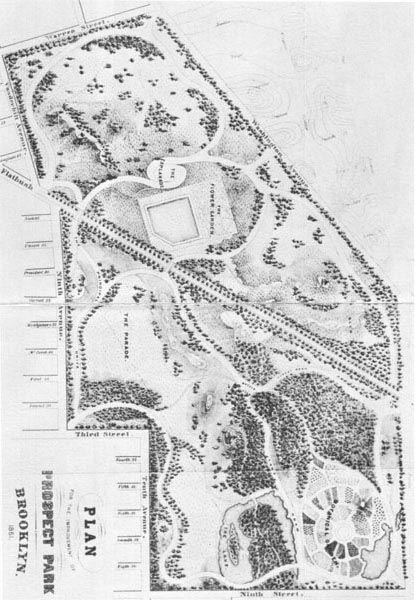

The plan for Prospect Park underwent a series of changes in the 1860s and 1870s. The first plan, by Central Park's chief engineer Egbert Viele, called for the park to extend as far north as Warren Street. (Prospect Street today.) According to this plan, 323 Prospect could have had faced Prospect Park. (Yet it wasn't built that way … .)

Egbert Viele's plan for Prospect Park, 1861. From NYC-Architecture.com.

Olmstead and Vaux's revision, as seen on the 1866 Johnson map, is the basis for the park as it is today. Yet there were also substantial changes made later — the construction of Eastern Parkway and the Brooklyn Museum, for example. Indeed, even if 323 Prospect Place was built according to the 1866 Olmstead and Vaux plan, there's no explanation as to why it would be at such an angle.

Finally, I returned to an early theory involving Brooklyn's longest and oldest street: Flatbush Avenue. The road that is now Flatbush Avenue was originally the southernmost section of a network of ancient Native American paths. Broadway, in Manhattan, is also follows part of this network, which reached as far north as Albany.

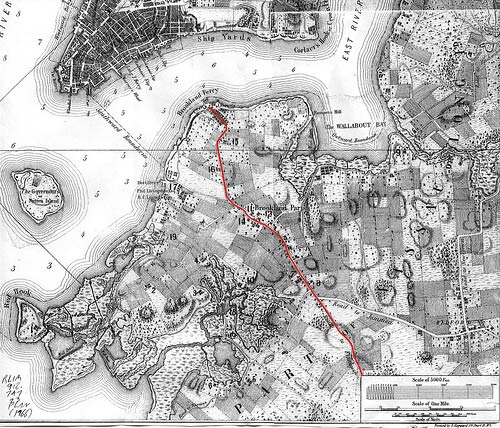

Brooklyn, 1766, 'Road to Flatbush' in red. This map is from the outstanding collection assembled by the Brooklyn Genealogy Information Page. Note the intersection of the 'Road to Flatbush' and 'Road to Jamaica' in the southeastern quadrant of this map — the intersection basically survives today where Atlantic Avenue meets Flatbush Avenue.

I thought that before Brooklyn evolved into its present layout, maybe Flatbush Avenue had been further east — perhaps this block was oriented to face the old right-of-way. Yet as I examined old maps like the one above, I was struck by how similar the old route was to today's. I abandoned this theory until I saw the map below.

Map of Prospect Heights showing historic route of Flatbush Turnpike and nearby plots of land, late 1800s. 323 Prospect Place in red box. Map from New

York Public Library; photo by Paul Proulx.

Over time, the "Road to Flatbush" became the "Flatbush Turnpike", and then finally Flatbush Avenue. The secret of 323 Prospect, as revealed in map above, has to do with the thoroughfare's evolution over time.

With the old farmland boundaries overlaid atop the late 19th century street layout, it becomes clear that the lost street is the Flatbush Turnpike. Even though 323 Prospect Place didn't abut the turnpike itself, the plot of land it sits upon is oriented with the surrounding properties to face the turnpike.

Thus 323 Prospect Place owes its unusual placement to the route of the Flatbush Turnpike. While the old property boundaries facing the old route of the road have had a broad impact on the area — especially the back property lines of plots on the west side of Washington Avenue — only the buildings around 323 Prospect Place are completely oriented according to the old layout. The reasons for this exception aren't clear — the mystery remains partly unsolved. Part of me hopes I never find the answer: that way I can keep on looking.

Back to Top

AUTHOR BIO:

Josh Jackson is a writer and planning consultant in New York City. He's worked with the NYC2012 Olympic Bid, Alex Garvin & Associates, and the Project for Public Spaces. He lives in Brooklyn and writes the Built Environment Blog.

LOST RSS Feed

LOST RSS Feed

LOST RSS Feed

LOST RSS Feed