LOST PERSON  |

FEBRUARY 2006 – NO. 3

|

Killing Our Elders

by Brenda Peterson

Losing our old forests is like sacrificing many generations of our grandparents all at once.

Recently, a friend and I drove through the High Sierra and Cascade forests on a road trip from Los Angeles to Seattle. In the four-hour drive between the old mining town of Yreka in northern California and Eugene, Oregon, we counted 50 logging trucks, roughly one every four minutes. Many of the flatbeds were loaded with only a few huge trees. On the mountainsides surrounding the highway, I was shocked to see so many clear-cuts, where once flourished ancient trees. Thousands of tree stumps bobbed across the barren hills like morning-after champagne corks. I don't know when I started crying, whether at the sight of crazy-quilt scars of clear-cutting or when we called our friend's cabin on Oregon's Snake River, outside of Merced, and he told us that every day, from dawn to dusk, a logging truck had lumbered by every five minutes.

"It's like a funeral procession out of the forest," my friend Joe said. "It's panic logging; they're running shifts night and day before the winter or the conservationists close in on them."

As a small child growing up on a Forest Service lookout station in California's High Sierras, near the Oregon border, I had believed the encircling tribe of trees were tall neighbors who protectively held the sky up over our rough cabins — "Standing People." For all their soaring, deep stillness, the ponderosa pines and giant Douglas firs often talked in the night, a wind language of whispers and soft whistles that sang through the cabin's walls.

In the daytime, I had memorized the forest floor. It smelled like pine sap and sweet rot, perfuming my hair, which was always tangled with bits of leaves, small sticks, and moss. It never occurred to me during those early years in the forest that I was human. To the old trees, I was perhaps another bobcat or burrowing bear cub, my small paws imprinted with pine needles and pungent dirt. Before I learned words, I listened to the piercing language of hawks and hoot owls, of thunder cracking tree limbs. As a toddler, I learned to stand by wedging my fingers into the craggy hand-holds of red cedar bark and pulling myself upright. I would balance better with one hand steady on the tree — a standing meditation I still do these 50 years later. Standing with the trees.

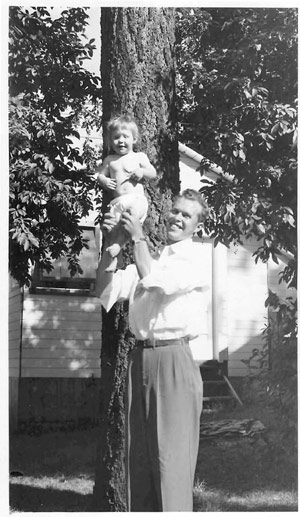

Author and father, Plumas National Forest, 1951.

Photo credit: Janice Peterson. |

As I drove that day through those once lush Oregon mountains, I noticed my fingers went angry-white from clenching the steering wheel every time a logging truck lumbered by me. I wondered about the loggers. Many of them, too, had grown up in the forest; their small hands had also learned that bark is another kind of skin. Among these generations of logging families, as in my own, there is a symbiotic love for the trees.

Why then this desperate slashing of their own old-growth elders until less than ten percent of these ancient trees still stand?

Amidst all the politics of timber and conservation, there is something sorely missing. Who are the trees to us? What is our connection to them on a deeper level than timber? In the 500,000 years of human history throughout Old Europe, the pagans worshiped trees. The word pagan means simply "of the land or country." When our ancestors recognized that our fate was directly linked to the land, trees were holy. Cutting down a sacred oak, for example, meant the severest punishment: The offender was gutted at the navel, his intestines wrapped around the tree stump so tree and man died together. Our pagan ancestors believed that trees were more important than people, because the old forests survived and contributed to the whole for much more than one human lifetime.

Between 4,000 and 5,000 years ago in our own country once stood a multitude of Giant Sequoias in the Sierra Nevada. Most of these great trees are gone, but in Sequoia National Park there is the General Sherman Tree. Thousands pay homage to it every year. And no wonder. According to Chris Maser in Forest Primeval: The Natural History of an Ancient Forest, the General Sherman Tree "was estimated to be 3,800 years old in 1968. It would have germinated in 1832 B.C. … [it] would have been 632 years old when the Trojan War was fought in 1200 B.C. and 1,056 years old when the first Olympic Games were held in 776 B.C. It would have been 1,617 years old when the Great Wall of China was built in 215 B.C. and 1,832 years old when Jesus was born in Bethlehem."

*

As we drove past the Pacific Northwest sawmills, I was startled to see stockpiled logs, enough for two or three years of processing. And still the logging trucks thundered up and down the mountain roads. To quiet my own rising panic over such a timber rampage, I tried to understand: "What if trees were people?" I asked myself. "Would we treat them differently?" My initial response was "Well, if old trees were old people; of course, we'd preserve them, for their wisdom, their stories, the history they hold for us." But with a shock I realized that the reason we can slash our old-growth forests is the same reason we deny our own human elders a place in our tribe. If an old tree, like our old people, is not perceived as productive, it might be disappeared.

Maturity teaches us limits and respect for those limits within and around us. This means limiting perhaps our needs, seeing the forest for the timber. If we keep sending all our old trees to the sawmills to die, if we keep shunting off our elders to nursing homes to die, if we keep denying death by believing we can replace it with what's new, we will not only have no past left us, but no future. A Nez Perce Indian woman from Oregon recently told me that in her tradition there was a time when the ancient trees were living burial tombs for her people. Upon the death of a tribal elder, a great tree was scooped out enough to hold the folded, fetus like body. Then the bark was laid back to grow over the small bones like a rough-hewn skin graft.

"The old trees held our old people for thousands of years," she said softly. "If you cut those ancient trees, you lose all your own ancestors, everyone who came before you. Such loneliness is unbearable."

*

Losing our old forests is like sacrificing many generations of our grandparents all at once; it's like suffering a collective memory loss. I could not help but ponder this vast loss when I read about the late President Reagan being felled by Alzheimer's disease. In an interview, his biographer, Edmund Morris, reported that Mr. Reagan had stopped recognizing him — " … I did not feel his presence beside me, only his absence." Morris then related a haunting scene: Referring to a set of his own Presidential papers, Mr. Reagan told Morris, " … move those trees." Morris commented, ''Well, if a poet can compare stacked volumes to garners of grain, I guess a retired statesman can call his collected works trees if he wants."

Mr. Reagan was, of course, correct — his Presidential papers were originally made from trees. But when I told this story to a South American who has spent many years studying with Brazilian shamans, she said softly, "Oh, your ex-president is like an old tree now, a grandfather who's fallen down and forgotten who he is."

She shook her head sadly. "Old trees hold us to the earth by their deep roots. And trees are our memories like the blueprints of our planet's history. When you cut those ancient trees, the earth loses its memory, its way of knowing who it really is."

As I drove across the Oregon-Washington border toward Seattle, where I have made my home for 25 years, I hoped to see fewer logging trucks rumbling by on the freeway. But here, too, was the silent thunder of fallen trees atop heavy trucks. Lumbering trucks.

The English word "lumber" has its roots in the pawnbrokers of Lombardy, Italy and once referred to stored and "discarded household articles, furniture … ." How did our ancient forests devolve, even in our language, from living elders to discarded lumber? How did Standing People lose their silent, soaring authority to fit our definition of a verb that means "to move heavily and noisily?"

As we drove, dodging logging trucks, I heard a radio report that a federal judge in my native California had temporarily stopped the Forest Service's "Ice Project" logging plan in Giant Sequoia National Monument in the hope of keeping intact a 1,000-acre preserve that holds two-thirds of the world's largest trees. Though much of this Sequoia National Forest is a national monument, this "Ice Project" timber sale was approved before 2000, when Congress declared this last stand of ancient trees a national monument. The report concluded that the Bush administration, "already under fire for its broad attempts to reopen Giant Sequoia to commercial logging, had tried to grandfather that project into the Monument boundaries" and logging had already begun in the area in September, 2005. Such groups as the Sierra Club and EarthJustice are fighting to keep the Giant Sequoia safe from logging.

Again, I felt that deep cut of pain at my roots that I always experience when I hear that this Forest Service, which employed so many people, including my father, who are devoted to trees, is also so much in the business of logging our forests. Do we always cut down our family trees? Must we always discard our elders when they begin to lumber along heavily with the wisdom and the burden of old age? Our children's generation is growing up with only the memory of ancient forests; they don't feel the presence of old trees — only their absence.

As I neared my Seattle home on the Salish Sea, I was passed by a logging truck with only one gigantic tree strapped on its long, metal bed. Was it perhaps a sequoia? The tree was so huge, its slashed circumference a spinning galaxy of pale age circles, a lost portal. No more sonorous deep breath, no more shade, no generous legacy of oxygen given us. I pulled to the side of the road, shaken, my head bowed. "Great-Grandfather," I said softly as the great tree passed, sideways, still.

This essay is adapted and updated from the author's essay collection, Nature and Other Mothers, which was published by Ballantine. © Brenda Peterson.

Back to Top

AUTHOR BIO:

Brenda Peterson is a novelist and nature writer, author of over 15 books, including the memoir Build Me an Ark: A Life with Animals, and the novel, Duck and Cover, a New York Times Notable Book of the Year.

LOST RSS Feed

LOST RSS Feed LOST RSS Feed

LOST RSS Feed