NONFICTION  |

SEPTEMBER 2006 – NO. 8 |

|

|

The Death of the Dream

The Farm

The old way of life, centered on the barnyard with its big red barn on one side and the modest white house on the other, has disappeared, and many of the most characteristic scenes of American life have disappeared along with it. There, washing hung on the line in the yard as the farmwife stood on the kitchen porch shouting at the children in the barnyard who, with the eager help of the farm dog, ran around in circles chasing chickens and raising the dust onto the washing. The farm cats sat and looked on disdainfully while the farmer himself toiled away out on the horizon cultivating the corn with his willful team of horses swishing their tails and stepping firmly along. Such images of farm life appeared in so many forms of American art and literature for so long that they came to be accepted as permanent, making it difficult to grasp the enormity of the fact that that way of life has gone now, and with it many of the qualities and values that made the nation great.

In the 1880s and 1890s about 43% of the U.S. population lived on farms. Today less than 1% of the population lives on farms, and those farmers do not tend to have many children who help run the farm. The total number of acres in U.S. farms reached a peak of 1,206,000,000 acres in 1954 and then fell to 938,300,000 acres by 2002, when there were still about 2,129,000 farms in the U.S. Many of the remaining farms grew larger by consolidating several old family farms into one new farm, which left several sets of the original buildings abandoned. Many of the abandoned farmsteads were vacated between about 1962 and 1975, which was also the time when the national economy evolved into its present post — industrial phase. Now a relatively small number of large companies produce the essentials of life — food, shelter, energy — while the majority of the people (about 80% in 2003) work in service industries that do not depend upon the production capacities of the nuclear family as did classic farming. To a substantial degree, the management of these remaining farms has been surrendered to the specialists of finance and technology, who cannot duplicate the productive vigor that characterized the classic family farm.

The Farmer

The man was the head of the traditional farm household. He went out from the family and engaged in physical interaction with the external environment to obtain food, created shelter using the most advanced technology he could obtain, interpreted his experience with the environment, and formulated the social values and philosophical convictions of the family. He was the source of the highest abstract principles with regard to the integrity of his word, the honor of the family, and the rectitude of the nation. If the family had a dreamer or an idealist it was likely to be the farmer, not the farmwife. He represented the family in all formal social activities, defended it from physical danger as well as legal attack, and made final decisions. He was always under pressure to work quickly and to work safely, without accident to himself, his family, or his animals, because help might be far away and he could not afford the cost of the injury or the loss of the time. He had to work fast and cheerfully and not blame his friends and family for his difficulties and disappointments, which required confidence, determination, forbearance, and a generally amiable disposition. He had to make his own decisions knowing that the welfare of his entire family depended upon them, and he had to work without a net of cash reserves or insurance policies to catch him if he fell.

The Farmer's Versatility

The farm was very much an industry or complex of industries that rewarded the versatile individual who had a mind capable of assuming broad responsibilities and making productive order out of the whole of life. The farm family could raise all the field crops, vegetables, fruit, and flowers in the bountiful seed catalogs as well as manage all the wild trees and plants in its locality. The classic farmer worked with living organisms all up and down the phyla from 2000-pound bulls to horses and pigs and birds and insects and microscopic yeast and bacteria and many different plants. The farmer dealt with them all for their meat, fat, leather, wool, fur, bristles, feathers, eggs, milk, cream, butter, honey, wax, fruit, juice, seeds, pods, leaves, wood, roots, and fibers. As the farm became more mechanized, the farmer learned to run and maintain more and more mowers, plows, harrows, seeders, cultivators, reapers, binders, cutters, pickers, pumps, mills, saws, grinders, engines, generators, and transmissions and to use all the fuels, tools, lubricants, and liquids that came with them. The Midwest farmer could do the work of dozens of today's specialists. He was a hunter, trapper, butcher, cowboy, teamster, leather crafter, veterinarian, nurseryman, gardener, carpenter, plumber, roofer, painter, blacksmith, mechanic, engineer, teacher, counselor, business manager, accountant, entrepreneur, and administrator. He worked with soil, water, wind, rock, wood, iron, steel, concrete, leather, paints, chemicals, and explosives — all of which had their own look and feel and scent and sound when they were worked with skill. He could use hundreds of hand tools ranging from the shovels, hoes, forks, and rakes of the soil to the axes, saws, knives, and planes of woodworking to the hammers, files, drills, and wrenches of metal work, along with many special tools like hoof cutters, spokeshaves, and ice saws.

Physical skill and mechanical invention were rewarded on the farm, and when men got together socially, they liked to talk about difficulties overcome and hindrances outsmarted by their horses or their machines or by clever tools and crafty methods of their own invention. If a boy showed himself to be bright, and a hard worker who never complained even when his finger got hammered, he would be allowed to sit on the fringe of these discussions and learn what a good man was like.

European visitors to the big wheat farms of the Red River Valley, which drained North Dakota, Minnesota, and Manitoba, were surprised at the extensive use of big complex machines almost never seen in Europe. Not only were the Americans running big machines, but they also were always buying bigger machines. Small farmers took advantage of the turnover and bought used machinery cheap, repaired it, and cycled it through their operations, and every farmer in the Midwest had a greater or lesser personal junkyard that supplied spare parts and looked like an ill-kept museum of technology. The farmers developed a whole tradition of Midwest mechanical ingenuity that later manifest itself in extensive contribution to the automobile and aviation industries.

The classic farmer generally worked at a regulated pace that allowed some time to perceive the subtlety of nature and the complexity of the intricately woven-together lives of the plants and animals. Good farmers might occasionally be seen simply standing out in their fields contemplating them. When the alfalfa is in bloom or when the corn is tasseling, a great fragrance rises out of the field and drifts and spreads on the wind, beckoning the insect populations to come for the nectar and pollen. If one stands quietly one soon becomes aware of the determined industry of dozens of different sorts of bees, flies, moths, and butterflies. The buzzing, scratching, rustling, and chewing is everywhere. The corn has sounds all of its own. In a dead calm on a hot July morning you can hear it grow. As it swiftly multiplies its cells and expands its leaves and stalks, they push past each other and the field is filled with faint creaking sounds. On a quiet winter day in the woods of the shelterbelt, you can hear the snow fall through tree branches — it hisses gently.

Most of the time, the wind is much too restless to allow such perceptions and instead busies itself driving in storms whose crashing and flashing thunder and lightning require no great sensitivity to be perceived. But the power and subtlety of his perceptions of the world made the farmer feel alive and a part of a symphony of organized energy and growth that fueled his faith in the future and his will to work.

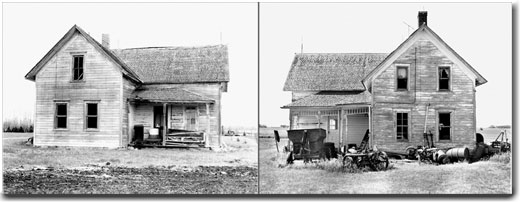

The size of this house is about the minimum at which it was practical to build separate rooms for separate activities rather than build a common room where one did everything. Here the four special spaces — kitchen, living room, bedroom, and porch — have been minimally distinguished. The specialization is incomplete because the kitchen is essentially a lean-to on the main house and the kitchen porch shares the kitchen roof rather than having a separate one of its own.

Big Stone County

When an L-house was built with a minimum sized kitchen, the living room had to serve as a common room where any indoor activity could be carried out; the other rooms were so small that they couldn't host their own functions alone. The kitchen is too small to contain a table to eat at, and the only bedroom in the house was up in the small second story, so it is likely that, on some occasions at least, someone slept in the living room.

Big Stone County

Farm Animals

Animals were involved in one way or another with all the work on the farm either as providers of work and food or recipients of it. They provided the power for all the transportation vehicles and field machinery, and their lives were closely interwoven with those of the family. Oxen, horses, cattle, hogs, sheep, and chickens had to be fed every day. Cows had to be milked twice a day, eggs had to be collected, calves and foals nurtured, hoofs trimmed and shoes fit, teeth filed, wool shorn, cuts and sores dressed, and tons of manure moved out of the barn and onto the fields.

Farmers achieved an understanding with their work animals based on mutual dependence. Horses and dogs had a considerable capacity to work with others, stemming from their herd and pack instincts; at the same time they were very much individuals. Farmers were perfectly aware of the individual identities and personalities of their animals, as we see in chattel mortgage papers, which list a description and name (like Bird, Bell, Barney, Queen, and Cap) for each horse put up as security for the loan. Horses with hostile dispositions might bite or kick or knock one down with a swing of their heads. Those inclined to show protest or resentment that way always had to be watched, because they could deliver very heavy blows resulting in broken bones. Such horses might still be kept because they could be strong workers as well as dangerous. Others had good dispositions but were lazy and when teamed up with other horses would only pull enough to keep the slack out of the chains without doing any actual work. Drivers of the large teams of 30 horses or more used on bonanza farms had to keep an eye out for individuals who simply strolled along with the crowd instead of pulling. Some drivers took along a pile of rocks with which to pelt shirkers to keep them on the job. Delivering such admonitions was touchy business, however, because if one hit an honorable horse by mistake it might startle him and confuse the team. If such a team began to run there was no way to stop it without tearing up the field and breaking the machinery.

Some horses thought that the work day was too long which resulted in crooked rows at the end of the day when they wanted to go home. They kept veering off so as to aim the row at the barn instead of keeping it parallel to the rest of the field. The farmer kept pulling them back on line, and they kept leaning off toward the barn, so one ended up with an undulating row as a record of the conflict of willpowers. Many horses understood their work perfectly and carried it out with little instruction and no coercion. When corn was picked by hand, for example, the horses drew a wagon down the rows for the pickers to toss the ears of corn into and because they wanted to put as many skilled hands in the field as they could (a good picker kept an ear in the air all the time), they trained the horses to pull the wagon ahead when they called "step up" to them. Smart horses would keep an eye on the pickers and move the wagon ahead to match the pace of the pickers without being told anything at all. The truck and tractor cannot provide such help. That cooperative spirit endeared farmers to their horses. When farmers had family photographs made they included their horses in the lineup of family members. Typically the order was farmer, farmwife, children in descending order by age, the dog, and finally the horses, who usually stood attentively, studying the photographer with their ears perked up because just before he opened the shutter the photographer would wave his coat in the air to get their attention, producing photos in which you can still make eye contact with each person and animal in them. The farmer's strength and masculinity were represented by the power and capability of his horses similar to the way automobiles have represented personal qualities and social status since then.

The Farmwife

The farmwife's sphere of responsibility was similar in magnitude to that of the farmer, but it had a different center. The farmwife created the physical and emotional environment of the home within the house. She guaranteed the maintenance of the proven, down-to-earth survival systems while the farmer pondered new systems and inventions that might contribute to the future success of the family. She managed the provision of food, clothes, warmth, and rest, and organized the house to be a secure base of operations for herself and her husband, for the bearing and rearing of children, and for the conducting of all physical and social operations internal to the family. She kept the subjective feelings and emotions of the inner life of the family directed constructively. She worked somewhat more instinctively than did the farmer, who analyzed the exterior world to assess which technology and political alliances would be most beneficial to himself and his family.

The farmwife was the nucleus of the entire farm. Her stove fired the glowing core of the life of the family, and her kitchen was the single most important place on the farm. The farmer's hopes and fears for the future were discussed at her kitchen table where most of the meals were served, where the children did their schoolwork, and where most of the cooking, canning, and sewing were done. All outsiders — visitors, tradesmen, neighbors, egg customers — first had to deal with the central coordinator, the farmwife, because even if their business was strictly with the farmer he was sometimes far away in the fields and only the farmwife knew where.

The farmwife assumed responsibility for maintenance of most of the family's social relations with the church, school, and relatives, and she might also keep the books and records of the farm and write most of its letters. If the flow of energy on the farm were likened to a musical composition, then the farmer played the melody while the farmwife kept the rhythm and tended to the harmony. She cooked, canned, washed, cleaned, sewed, and mended, and looked after all the needs of the children, including breast-feeding and diaper maintenance, without help except from relatives. She kept the gardens, tended bees, raised chickens, gathered eggs, churned butter, and refilled kerosene lamps and cleaned their globes. She carried out dozens of household chores without plumbing or electricity. She did have a number of simple machines to help her, but every one of them had a lever or a crank or a treadle that she had to activate with her own power.

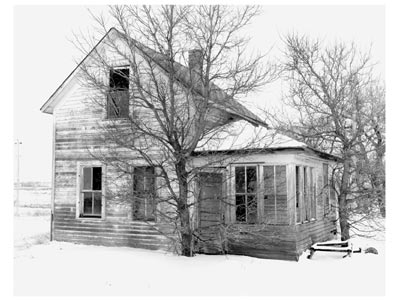

Often the porch is the only part of a basic or simple L-house that saves the house from looking plain and characterless. In this view, the porch appears to be built of nothing but a roof and two posts, but those elements are nicely proportioned and balanced so the space they define has a comfortable and inviting look that enhances the hospitality of the house. The weather has dismantled the room of the house and revealed how many hundreds of small individual pieces were put together to complete the roof as a whole. The trend in modern house building is to use big, pre-manufactured pieces, like 28' roof trusses and 4' by 8' chipboard panels, while in the past, ten to 100 small pieces would have been hand-assembled onto the house.

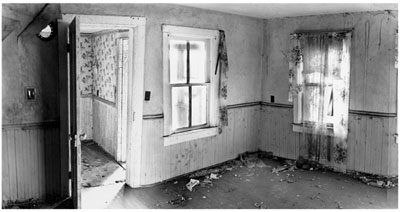

Very few rooms remain today that still contain the furnishings of the way of life before the installation of plumbing and electricity. The old kitchens usually had a stove in the middle of one wall (so the chimney rose through the roof ridge above the centerline of the kitchen), a sink in the corner, and a relatively large workspace in the center of the room. When this kitchen was abandoned, the occupant was still cooking on a wood-burning stove, although this stove was being fired with corncobs and charcoal rather than wood. Dry corncobs were good fuel, and these stoves were advertised as being designed to burn wood, coal, or corncobs equally well. The presence of all these objects is evidence of the variety of physical labor that was required to get clean water and sound fuel into the kitchen and wastewater, garbage, ashes, and smoke out of the kitchen safely. The doorway at the far right leads to the living room. The door to the right of the stove leads to the cellar stairway, and the door behind the stove leads to the back bedroom and also to the second floor stairs. The door furthest to the left leads outside towards the driveway and barnyard.

The farmwife maintained the unbroken flow of effort on the farm uninterrupted by vacations or extended leisure time. Rest, regeneration, amusement, and delight were natural elements of farm life integrated into production and not separated from it or opposed to it. The farmwife's work was never done because the family aspired to accomplish more than it could actually complete at any given time, and even if the farmwife did get caught up, it wasn't for long, because the farmer and the children looked to her for steady emotional support and help with their work on top of her own. She was the first one up in the morning and the last one to bed at night and was generally on call for any emergencies during the night as well.

She had fewer breaks in her routine than did the farmer, who had occasion to go to town on business or go see a neighbor to arrange for help or drop in the saloon to talk about weather, prices, and politics. The women were not as mobile as the men and were sometimes isolated on the farm, which caused them some loneliness and sense of oppression if they had overbearing husbands. They were not slaves to the farmer, however; they were partners in a demanding enterprise whose challenges brought out their strengths and obliged them to take charge of the household and run it rather than let it run them. The work of the farmwife was done for the good of her own family in her own house, and she allowed very little of the energy expended by the family to go into counterproductive internal dissent or external bureaucratic exercises; none of it was to be exploited by an outside employer.

Persons who worked with farm women on classic farms say that, in retrospect, they simply don't see how the women got so much done or when they got enough sleep to keep doing it. Successful farmwives were adroit family managers who wove together many different streams of effort and persistently maintained the unbroken flow of interaction with the environment. That unrelenting maintenance, no matter how bad things got, was both the curse and the glory of the farmwife's life. When one reads the memoirs of farm women who lived through the hard times of the 1930s, for example, they often give sobering accounts of toil and trouble and fear and heartbreak, but they did get their families through, and they often note, a little surprised at themselves, that those were the best years of their lives.

Farm children contributed to the success of the farm by doing real work. They pumped water, cut wood, carried out ashes, rounded up cows, cleaned out stalls, fed chickens and pigs, weeded gardens, picked fruits and vegetables, brought in ice, ran errands, and helped their mother in every way she asked. The girls learned cooking, canning, housekeeping, and homemaking from their mothers and the boys learned all the outdoor responsibilities from their fathers. A farm boy was of real help to his father and would work right along beside him in natural apprenticeship, eagerly anticipating what he could do next to earn the respect of the men. Farmers might say that a particular job required two men and a boy, indicating how much of it was hard, skilled labor and how much was unskilled assistance like handing tools, holding horses, carrying messages, and unloading wagons. The farm boy learned by example from daily experience on the job, not from overspecialized institutional authorities short on practical experience, and he could be praised for hard work and bright insight immediately and not be kept from his life's work by the need to spend years obtaining academic credentials at a university.

Contemporary children have comparatively little productive function in life and consequently become inert pawns in the games of adults rather than independent entities with productive lives of their own. Young people do not yearn to work the soil with their hands; they yearn to go to California and become stars in the sports and entertainment businesses, possibly in pornographic movies and prostitution when no other opportunities can be found, or to become high-income attorneys to take part in all the nation's litigation. The old virtues so critical to farm life are unimportant in an affluent culture where manipulation of wealth, not the production of it, is the crucial activity.

The classic family farm was never idyllic, never the scene of pastoral idleness, and never completely independent and sufficient to itself alone. It was an economic enterprise based on the strenuous application of all the resources an individual possessed, which made it a great opportunity that brought out the best in a great many people. That does not happen in the life of corporate or institution employee of today who is obliged to exploit a few capabilities and suppress the rest.

The L-house on the Prairie

The great majority of the houses of western Minnesota were cheap, plain, awkward, and unlovely. Harmony and unity did emerge from the mundane clutter, however, in the form of the classic L-house, which became representative of much of the farming way of life in the Midwest. When the prairie farm families earned enough money to move out of their cabins and sod houses, they often built modest rectangular shaped one-and-a-half-story houses with simple gable roofs that became L-houses later on when their owners again earned enough to add on the kitchen L and the porch of a complete L-house. In other cases people lived in their sod houses until they had enough money to build a complete L-house all at once. One farm couple remembered that their family's L-house was said to have been built by seven men in seven weeks for $700.

The prairie farmhouse was not like a Medieval European peasant's house, with its massive oak timbers and full thatched roof that sloped almost to the ground and sheltered one large space for both people and animals with an open fire pit in the center; nor was it like an American colonial farmhouse, with its large walk-in fireplace, massive chimney, oak beams, and stone floor. In those houses, the hearth was the heart of the home and the materials to build the house were taken from nearby forests. Each piece was hand-formed before it was fit in place, and the finished house became almost a part of the land.

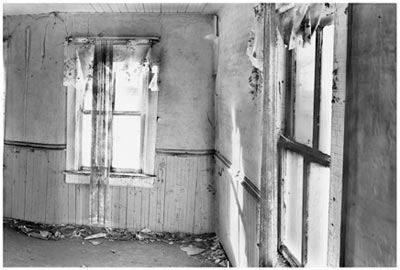

Compared to Medieval European houses, American L-houses were light assemblages of industrially produced sticks and boards that formed boxes with hollow walls. These walls were grouped together to form a house lacking a powerful skeleton.

The classic farm was a structural species with a lifespan, and it evolved through adaptation to a specific set of economic conditions. Classic farm life on the prairie developed quickly and produced only one wave of characteristic architecture. Once the hunger of world markets for wheat was satisfied by the initial exploitation of the virgin land, the motivation to generate an original regional economy diminished and indigenous architecture ceased to be produced. There was nothing built there before the farmers came, and nothing built there since that time really belongs to the region. The realization of the dream consumed the basis for the dream, and the next dream has not yet formed.

Adapted from The Dream Unabridged, a large-format sequel to the book, The Death of the Dream, by William G. Gabler, featuring text and photographs. Copyright © 2006 by the author. Please contact general@lostmag.com with inquiries about ordering an author-produced copy of The Dream Unabridged.