| 2011 WINTER EDITION – NO. 42 |

Disappeared Detroit

The odometer rolled over on another modern era with typical to-the-minute precision: "For Detroit, the 20th century ended at 5:47 p.m. October 24, 1998." True to form in the Motor City — mythic land of the annual new model — Detroiters got a head start on the coming century as the rubble met the road. "With a deafening roar that will echo in the hearts of Detroiters for decades," said the local press, the long-barren J.L. Hudson Company department store careened its way into the dustbin. "Explosions raced across the building, shearing off pillars as they moved northwest: men's suits on two; junior dresses on five; the community auditorium on 12," until even the cork-lined fur vaults on the 17th floor (capacity: 83,000 furs) blew apart and "the mammoth structure wobbled like a drunk, hesitated, then collapsed into a 60-foot-high pile of rubble." 1 The sprawling, 28-story downtown emporium had been branded "the symbol of one of the most notorious episodes of urban decay in America's history." 2 The store hit its peak sales year in 1953, and it was all downhill from there. Its bronze doors slammed shut for good in 1983, entombing memories of Santa Land, elevator ladies, and Maurice salads within its brooding shell — a "decrepit behemoth's carcass," detractors said, blighting the city. The Downtown Development Authority wanted it blitzed. The Loizeauxs were happy to oblige.

Standing 439 feet tall and sprawling 2.2 million square feet — the second-largest department store in the nation, after Macy's in New York — Hudson's was billed as "both the tallest and largest single building ever imploded." 3 (Taller stacks had been downed, but this was the tallest once-inhabited structure. It remains a matter of industry bickering over who takes the cake for the largest single building blasted, with Hudson's and the Sears center in Philadelphia, razed in 1994, vying for the title.) The formidable building, constructed over 12 stages between 1911 and 1946, had 76 elevators, 705 fitting rooms, and a women's restroom boasting 85 stalls. It took 21 workers nearly three months to scout the structure, plus four people to work up the implosion, which was fired by 2,728 pounds of explosives. "It's the most we've ever used for one building anywhere, anytime, anyhow," Mark Loizeaux said. 4

When the big day finally came, television anchors were rushing to complete their own hectic preparations as they juggled the once-in-a-lifetime implosion with the all-important Wisconsin-Iowa football game (one news director vowed to run both ratings-grabbers live, using a picture-within-a-picture insert). But you didn't need a wide-angle lens to catch the broad smile on the face of then-mayor Dennis Archer. Radiating bliss at the downtown redevelopment prospects opened by the 12 million dollar blast, Archer grabbed Doug Loizeaux in a hug as they watched atop a nearby building, pumping his fist when Hudson's tumbled into a 330,000-ton pile of history. Visions of the office-retail complex that was slated for the site — ironically called Campus Martius or "field of Mars," named after the Roman god of war — must have danced amid the detonating charges as Archer punched the ceremonial ignition switch. "Today, we say goodbye to years of frustration," he declared. "Let the future begin." 5

As the blast commenced and the "symphony of failure" reached its crescendo, spectators duly took note. "It sounded musical," sighed one rooftop partier, munching on shrimp and pastries. "It was so graceful." 6 As it happened, there was an added tinkling effect when the 27.7-second blast shattered 132 windows in surrounding vacant buildings. The Loizeauxs said that 92 windows were already cracked, and they expected the breakage, which they thought would cost about $10,000 to fix (seven separate glass companies were already on high alert for the occasion). The sheet music took a more consequential detour, however, when six columns went akimbo during the implosion and landed on a nearby concrete box girder, knocking out service on a 350-foot chunk of Detroit's elevated People Mover railway, only a dozen feet away. ("The People Mover won't be moving any people for a while," was the press's mordant take. 7) After an initial glance, a manager downplayed the damage as "cosmetic," but it ultimately took a year to fix the line and restore the system to full capacity, irking Detroit bigwigs who claimed the incident cost one million dollars in lost People Mover revenue, stymied thousands of riders, and just plain looked bad. After various lawsuits, quarreling engineers, and sparring insurance companies had all been accounted for, the total bill came to more than four million dollars.

You might call it the curse of Martius — and he wasn't finished with Detroit yet. Moments after the blast, carousing crowds were abruptly confronted with a ten-story-tall dust tsunami emanating from the building, which "hurtled swiftly toward spectators to the south and east," a witness recounted. "[Mayor] Archer ducked into a stairwell while nearby construction workers stood their ground, toasting with Budweisers as gray soot enveloped them." 8 Other spectators, too, seemed to take the deluge with impressive savoir faire. One seasoned blast junkie came armed with mask, goggles, hard hat, and buttoned-up overcoat, so amply fortified she was dubbed "Miss Implosion" by envious friends. Meanwhile, 67-year-old Joyce Hurthibise bore the billowing cloud with stoic good cheer. "To see that building come down and then that cloud come at you, was just the most amazing thing I've ever seen," she said. "When the dust started coming, we just turned our backs to it." 9 There was even a silver lining for restaurateurs at nearby Greektown eateries, who were swamped by an early-dinner mob: folks diving for cover ended up lounging around for drinks and a meal. "It helped us because it happened during a time that is usually slow for us," said the manager at Trappers Bar and Grill. 10

Not everyone was so blasé about it, though; what some called the "attack of the killer dust" darkened the skies, sending a few spectators fleeing in fear and driving others into coughing fits. "The 50,000 guests followed the mayor's lead to come downtown and party," one resident later complained. "Surely, they had no expectation of the black cloud of dirt. It is these kinds of surprises that give rise to panic." 11 Though the blasters warned that dust would blanket the area and advised those with respiratory concerns to shun the spectacle ("This is not a publicity stunt," they said a week before the blast 12), that didn't stop television stations from helpfully rushing dust samples to waiting labs and reporting lead levels of more than 500 parts per million, enough to "cause serious damage" if ingested, according to one environmental expert. 13 While dust samples did turn up lead and asbestos, further analysis concluded, it was "not enough to be a health hazard for those who watched the downtown Detroit implosion." 14 City, county, and federal environmental officials all agreed, claiming that peeling lead paint in an old home would pose a much greater danger than the Hudson's dust, not to mention the months-long exposure to dust that a wrecking-ball-style razing would entail. Nonetheless, a lawsuit was promptly lodged against the demolitionists by a spectator alleging "unspecified injuries as a result of contaminated dust particles being heavily emitted into the air of the general public." 15

That suit didn't get very far, but the fallout over fallout went on for days, with some judging the dust episode a media-brewed tempest in a teapot. "Detroit makes a perfect laboratory for studying mass hysteria," one Michigan attorney commented, "thanks to some irresponsible TV news coverage of the aftermath of the imploded J.L. Hudson Building." Amid breathless accounts of toxic dust loosed upon the city from the sinister-looking cloud, the Hudson's terror could be a case of "hysteria-induced illness," the attorney wrote, owing mainly to a dour-looking doctor who popped up on Channel 4— clad in an authoritative white coat — discoursing gravely about stomach pains, headache, and fatigue. Asbestos is a serious health issue, no doubt, but depending on the financial rewards, "The syndrome may spread to people who were nowhere near any dust cloud," she wrote. "And soon there are class-action lawsuits." 16

Martius finally relented, it seemed, and the media soon blipped off to other pressing matters (Boy Sprays WD40 in Teacher's Sports Drink, the headline read one day later). The Hudson's smoldering remains, meanwhile, yielded up some crowd-pleasing artifacts, which Homrich Wrecking, the Detroit company overseeing the demolition, offered to local charities. More than 2,600 bricks from the site were sold off at an area Goodwill store in two days at five dollars a pop. "The newest fad?" You guessed it: "A hunk of rubble from the Hudson's building." 17 As the loss of the beloved structure soaked in around the nation, however, the high-fives gave way to melancholic afterthoughts. "A piece of me died when I saw on national television the implosion of the venerable Hudson's department store," a former Detroiter wrote in from Austin. "I certainly hope that somebody was astute enough to rescue the ornate brass drinking fountains scattered through the store. They were lovely." 18 The copper and brass fixtures, it was said, had long since been stripped out by vandals.

The demise of Hudson's (more a drama-drenched opera, as it turned out, than a symphony) may have blasted Detroit out of the 20th century, but the implosion was well in keeping with an august city tradition. When in 1979 the J.L. Hudson Corporation tried to take a wrecking ball to its opulent but failing department store, an architect, Lewis Dickens, campaigned to save the venerable redbrick pile. He began riffing on the shifting syllables of the city's name. "When the French were here, Detroit was pronounced 'De-twah,'" he told a preservation council. "Then it was 'Detroit,' and then it was 'Dee-troit.' Let's not now make it 'Destroyed.'" 19

Fifteen years later, Detroit had become synonymous with destruction. Architect Dan Hoffman, ruminating on the disappearing city, put it most poignantly. "Unbuilding," he said, "has surpassed building as the city's major architectural activity." 20 Between 1970 and 2000, more than 161,000 dwellings were demolished in Detroit, amounting to almost one-third of the city's occupied housing stock — that's more than the total number of occupied dwellings today in the entire city of Cincinnati. 21 Between 1978 and 1998 only 9,000 building permits were issued for new homes in Detroit, while the city doled out over 108,000 demolition permits. 22 "Demolition is so much a part of the city's culture," an investigative report concluded not long ago, "that in 2001, when he was running for mayor, Kwame Kilpatrick pledged to knock down 5,000 abandoned and dangerous buildings in his first year in office. After he was elected, he found there wasn't enough money in the budget to fuel such a ravenous demolition machine." 23

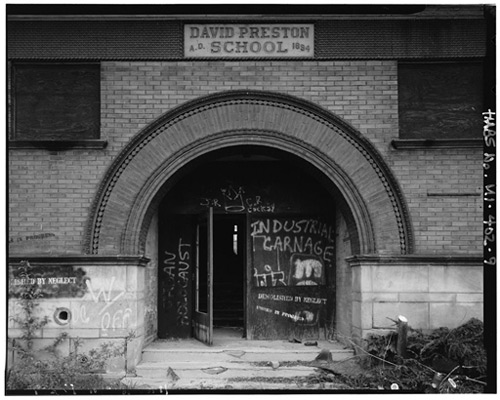

Detroit is disappearing because Detroiters themselves have disappeared. The city has shed 48 percent of its population — almost 900,000 residents — since its population peak in 1950. And they didn't all move back to France. Like many a metropolis of the era, against a background of shifting economic fortunes and stark racial divides, Detroit was walloped by "a five-decade exodus of middle-class families to the suburbs." 24 Its 139 square miles of turf, once upon a time the province of elegant Queen Anne duplexes and gabled Flemish houses and stout Georgian piles with Palladian windows, went into terminal shock. Bungalows went belly-up; cottages crumbled. The diagnosis: demolition by neglect. Fleeing owners sometimes ditched their houses altogether; others bailed out after defaulting on mortgages; still others sold to scurvy real-estate types, who wrung some income out of the properties and then bolted. The cycle was wearily familiar to the city's swamped demolition-permit department: "An owner would default; the property would fall into the hands of the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development; HUD would give it to the state, which would then give it to the city; and the city would demolish what by then had become a dangerous vacant building." 25 By that time, of course, scavengers had ripped even the bricks out of the walls and sold them to builders, who paid $200 for a thousand-piece lot. Whatever rubble remained was dumped into the basement, and the whole mess topped off with dirt — a cheap demolition trick, as we have seen, that drove up redevelopment costs because a builder would have to haul out the debris. The tainted properties languished, and the owner next door would start packing up. As one analyst summed up the city's predicament: "It does gravitate to a graveyard spiral." 26

Adding fuel to Detroit's great bonfire of unbuilding was, well, fire. In an annual rite on October 30, the night before Halloween, thousands of torch-bearing arsonists and riled-up spectators would take to the streets in a frenzy known as "Devil's Night." On October 30, 1984, the city's worst night, 810 fires burned over the three-day Halloween period in a ghastly bacchanalia that seemed to clinch the city's slide off the deep end. Some torched their own properties for profit; others just got kicks from watching abandoned houses go up in flames. Suburbanites would even drive downtown to enjoy the fray. "Some people like the Fourth of July," a resident of suburban Warren explained as he videotaped a blaze. "I like Devil's Night." 27 Over the years, the city struggled mightily to stamp out the menace — a chief tactic being yet more demolition, a sort of preemptive strike that would deprive the arsonists of their quarry. As part of its "Angels' Night" campaign in 2001, for example, during a three-day period officials wrecked 716 vacant structures (and towed 2,060 abandoned vehicles for good measure). 28 Critics pointed out the rather ironic fix in which the city then found itself. On the one hand, officials deplored the wanton torching of their urban assets, while on the other they "privately corroborated" the arsonists' illegal activities "by developing, funding, and implementing one of the largest and most sweeping demolition programs in the history of American urbanism." The upshot was painfully clear: "Vast portions of Detroit were erased through this combination of unsanctioned burning and subsequently legitimized demolition." 29

Many houses that did get torched would simply be left to rot, much to their neighbors' consternation. This proved a source of further unintended ironies in Detroit. What with an endless backlog of buildings to demolish — and often no budget for the bulldozers — the city was not known for rushing wreckers to the scene after a call came in from a burned-out citizen. Dan Pitera, who directs the Detroit Collaborative Design Center at the University of Detroit Mercy, sensed a creative-destructive opportunity at hand. "If you look at a burned house," he once told me, "they actually can be quite beautiful, if you don't have the negativity of what it means for them to burn." So Pitera and colleagues launched the "Fire-Break" project, a series of installations in and around picturesquely charred houses on Detroit's east side. Working with community members, they created sites such as the "Sound House" (where musicians from the neighborhood played Cajun tunes, while brightly colored fabric hung from its openings) and the "Hay House," covered with 5,000 tiny bundles of hay in a nod to urban farming. (In the city's fallow building lots, alfalfa is a popular crop, as it helps detoxify contaminated soil. It's hard to believe, but numerous residents have also turned derelict "crack houses" into "hay houses," used to store bundles of hay.) "We do all this without permission," Pitera explained. "They're intended to be mercenary acts." They hit their mark. In some cases, neighbors had been clamoring for years to get these particular houses destroyed, and a little art worked wonders. The design group's installations attracted the eye of city authorities, who sacked the structures within weeks. "Every house we've done so far has been demolished," Pitera said proudly. "When you consider there are 8,000 houses and we've gotten five torn down, it's pretty daunting."

Whether via neglect, fire, or the odd Cajun musician, block after block of Detroit succumbed to the bulldozer over the decades, but it wasn't until Monday, April 26, 1993, during a budget presentation to Detroit's City Council, that the city's unbuilding binge rocketed to national attention. On that day, Marie Farrell-Donaldson, Detroit's ombudsman, proposed that blighted sectors of the city be put out to pasture. Detroit would literally be downsized — "20, 25 blocks or so at a whack." 30 The plan called for residents to be ferried from moribund districts to those where a spark of life could still be found. Derelict houses would be demolished, empty stretches fenced off, and the whole mess turned over to "nature." Farrell-Donaldson, a former city auditor who was Michigan's first black female certified public accountant, titled her report "Management by Common Sense." She explained in terms familiar to the Motor City's hard-pressed automobile executives, "What we would be trying to do, in reality, is to downsize the community. We're talking about rightsizing the city to correlate with our budget." 31 It was an oddly intriguing idea — in some quarters, anyway — and proponents pointed out that "mothballing" was a common practice for bombed-out neighborhoods in European cities after World War II. If it's good enough for Dresden, it's good enough for Detroit. Demolition costs for the project were put at up to $4,000 per house, but since the city was spending four million dollars each year to maintain its 66,000 vacant lots, this was a modest sum indeed. Plus, wrecking one-third of the city would make vast parcels of land attractive to developers. 32 Having got hold of the story, the Economist mustered a stiff upper lip, concluding that "wholesale abandonment of parts of the city begins to make grim sense." 33

Official reaction around town was frosty (city budget director Ed Rago rebuffed the plan as a "bizarre notion") and editorialists blasted the proposal as a wrong-headed "clearance sale for Detroit." 34 But the scheme kicked up unexpected enthusiasm among the bombed-out sectors under discussion. "The mayor thinks it's ridiculous," one reporter wrote, "but some residents are asking, 'When's moving day?'" 35 So bitter had Detroiters become over pothole-pocked roads and weed-choked lots that the destruction of their own houses made perverse sense — especially if the city bought them out at a premium. "I've suggested to the city that they tear down more houses because there are too many blighted areas now," said one supportive homeowner. "Maybe some of the people who live next to these (fenced-out areas) can throw some grass seed in there." 36 That attitude showed outstanding pluck, but others were more noncommittal. So much demolition had already taken place, some said, that it had made the old neighborhood downright homey. "Now everyone has moved out and everything has burnt down," mused 73-year-old Bessie Graves. "It's a bit like living in the suburbs now. You could say it's almost a better neighborhood." In 1993, Graves' house — the one "with peeling yellow paint and a roof that sags almost comically at both ends" — was the only one left standing on the block. 37 It was the same story for Delores Reese, her home flanked by the hulks of houses destroyed by arson. "When people come to visit, I tell them to look for Little House on the Prairie," she said with amazing good humor. "It's like living in the country." 38 She wasn't exaggerating. At that time there were 65,000 vacant lots in Detroit, and the whole city was reverting to what it must have looked like when the French were wandering around the place and calling it "De-twah." "Covered by huge fields of brush six feet tall, many Detroit neighborhoods resemble prairies," one observer said. "Houses squat like pioneer outposts amid sprawling expanses of white Queen Anne's lace, blue cornflowers and other wildflowers." 39

The notion of full-scale urban clear-cutting may have shocked Detroit's polite society, but the concept wasn't exactly new, even for Detroit. Three years earlier, the City Planning Commission had prepared a report — apparently quickly buried — that has become known as the Detroit Vacant Land Survey. This remarkable document for the first time assembled maps of the city showing its vacant parcels, which were blacked-out with marker in ominous expanses. The report is full of disarming bureaucratese —" ...Master Plan proposes concentrating spot demolition of vacant structures along with a vacant lot cleanup campaign ... the few remaining families should be encouraged and assisted in moving into better housing ... over 70 percent of the parcels in the area are vacant ... simply vast areas of open space ... future of the remaining residential area remains unsure … ." 40 — that nonetheless proposed a revolutionary program of urban non-renewal. Observers later admired the document's "unsentimental and surprisingly clear-sighted acknowledgment" of the post-industrial maelstrom that had bled the city of its building stock, to say nothing of other basic resources. For once, planners had boldly come to grips with the "urban erasure" that had already taken the city by storm. 41

Prior to Detroit's woes, no city knew urban erasure like New York, and Farrell-Donaldson could easily have gone to Gotham for backup in the matter of demolition-minded urban remedies. In 1976, for instance, New York City began "thinking the unthinkable" when its top housing official, Roger Starr, urged all sensible Americans to get hip to the thought of "planned shrinkage." The city already had pockets of dwindling population — namely the South Bronx and Brooklyn's Brownsville neighborhood — and if you can't beat 'em, join 'em. Public policy would accelerate that shrinkage, so that blighted areas could be scratched off the list of neighborhoods needing expensive city services. 42 No doubt about it, Starr said. "The stretches of empty blocks may then be knocked down, services can be stopped, subway stations closed, and the land left to lie fallow until a change in economic and demographic assumptions makes the land useful once again." 43 It was strong medicine for an American dream obsessed with building up and growing ever bigger, as Starr himself acknowledged. "I surely cannot underestimate the fears engendered by this notion of growing smaller," he said, "in a social milieu in which growing bigger has been the hope of those who have not had a fair share." 44

This romantic vision of destroying the city in order to save it continues to tantalize urban thinkers. The scholar Witold Rybczynski was still working out the finer points of the concept just a few years after Detroit's dust-up over downsizing. The de facto abandonment of America's corroding cities was to be encouraged, he said, echoing Starr's bold thesis. "Housing alternatives should be offered in other parts of the city, partly occupied public housing vacated and demolished, and private landowners offered land swaps," Rybczynski wrote in 1995. "Finally, zoning for depopulated neighborhoods should be changed to a new category — zero-occupancy — and all municipal services cut off." Thus was born the dream of the "comprehensive downsizing of cities," an urban slash-and-burn operation that made Detroit's demolition binge look like kid's stuff. 45 Meanwhile, captivated by this apocalyptic panorama of "de-densified" cities wrecked beyond all hope, still other scholars have tried to get a grip on the broader phenomenon of "shrinking cities." Pointing out that shrinkage is a growing, worldwide affliction — the United States, Britain, and Germany are faring the worst, but places as disparate as Phnom Penh and Johannesburg have shed more than a third of their population — this camp reports that for every two cities that are growing, three are shrinking. And that's a recipe for destruction. "Traditionally, urban planners advise bulldozing eroded neighborhoods and starting from scratch," said Philipp Oswalt, project director for the three million dollar research project earnestly studying the newly diagnosed "shrinking city syndrome." 46 As in so many things, it seems, Detroit was ahead of its time.

In an extraordinary series of reports in July 1989, the Detroit Free Press counted 15,215 empty buildings in the city, a cancer the paper called "an infection more pervasive than ever documented" and testimony to the exodus of middle-class families "that is both a cause and a result of the economic decay that has crippled many Detroit neighborhoods." 47 The saga of Detroit's struggle to demolish this staggering inventory makes for one of the oddest episodes in modern urban history. It's a Pilgrim's Progress of vigilante wreckers and emergency demolition orders, a perilous journey through the eye-opening wilds of what one writer called Detroit's "spontaneous evolution of aggressive dismantling." 48 The city had plunged into the slough of wrecking despond at least as early as 1958, when a survey estimated that it would cost $1.2 billion to raze all of Detroit's blighted buildings — that's 60 million dollars a year for 20 years. By the time of the Free Press survey, however, officials had gotten a little behind in their demolition payments. At that time Detroit had razed an average of 2,000 buildings a year since 1982 — at nine million dollars per year, or $4,500 per home, a figure that had shot up more than 50 percent in five years. That was serious wreckage, the paper reported, but it wasn't even holding the line. Every year in Detroit an estimated 2,400 structures became newly vacant and in dire need of destruction.

There was smashing to be done, and Detroit rolled out the wreckers. In April 1989 Department of Public Works Director Conley Abrams was appointed the city's demolition czar, and he drew up separate demolition contracts for the city's four quadrants. The deal was this: each of the four contractors had to wreck at least ten houses every week; within each quadrant, smaller wrecking firms were contracted to raze three buildings per week. As part of the new blitz, crews were free to crunch up multiple houses in the same area simultaneously, which was a boon to wrecking productivity: one crew ripped down five "dangerously abandoned" houses on one block in just four hours. The city was justifiably purring over this lightning-speed action, but given the gargantuan task before them, it was no surprise that expectations might run a tad high. Just months after the bulldozers were unleashed, Curlee Shorter, a 12-year veteran of northeast Detroit, could be found in his front yard sounding off about a half-story-high pile of rubble mounded up next door. What with the slam-bam wrecking pace, a vacant house had been demolished by mistake; no one even bothered to haul away the debris, which was perfectly framed by Shorter's dining-room window. "You're sitting here eating and you've got to look at that," he said. "And the rats. We even killed some possums." 49

But at least that house got wrecked, even if it was the wrong one. Other Detroiters weren't so lucky, and they were taking blunt tools into their own hands. Disgusted by waiting for the city to demolish houses that had been on the to-be-wrecked list for over a year, by early July two posses of self-appointed "house-busters" had descended upon three long-vacant structures, one of them a crack haven and the others fire-damaged rat warrens. Jubilantly bashing away with sledge hammers, crow bars, baseball bats, and their own vans, they toppled the hated houses and hauled the debris into the middle of the street, smugly forcing the city to cart it off. The scene was one of lawless frenzy, crossed with some sort of neighborhood demolition-industry recruitment drive. "I saw them working and there was nothing else to do so I came to help," nine-year-old Roscoe Childs explained when reporters caught up with him. Others were simply aglow with that primal wrecking euphoria. "I'm ecstatic," 24-year-old Karen Reeve said. "I'm on top of the world right now." 50

The high was contagious, and soon roving, 30-person-strong gangs of what the media was calling "residents-turned-amateur-demolishers" were stalking the city with chainsaws. The "do-it-yourself demolition bug" was particularly catching among teenage boys. "We always bust up this place," explained 13-year-old Devin Laird, who boasted that he had started the whole craze by throwing rocks at one of the neighborhood eyesores. "Now everybody's doing it." 51 One civilized group of residents circulated a petition to get a consensus of 22 signatures on their block before dragging an offending house down, and the sudden blush of high-spirited cooperation seemed to put a spring in the whole city's step. Police cruised by amateur wrecking sites without stopping, and neighbors didn't even care when a wayward plank smashed out a window or two of their own basements. Meanwhile, demolition supporters pledged to post bail for comrades who might get arrested. "They're sticking their necks way out, and they're brave to do it," affirmed a 73-year-old. "They're helping the city out. It's not illegal." 52

Professional wreckers were slightly less gung-ho about this upswelling of sledge-hammer swinging competition. Larry Lewis, then director of the Inner City Black Wreckers Association, urged the demolition vigilantes to cool it for their own safety. "It's a risky business. Once you start to tear down a house, it could fall to the right or left," he said. "It's not predictable. It can fall on a fence, another house, or a person." 53 There was also fretting about live electrical wires, gas main explosions, and burst sewer lines. But no one could seem to get too worked up about the lurking hazards, least of all city officials. City Councilman Jack Kelley, having made the rounds of the wrecking sites, wistfully remarked that if there was a vacant house next door to his own home, he'd be first in line. "I'd get five gallons of gas, call the fire or police and I'd take it down very quietly," he said. "I know that's wrong, but you can't blame them." 54

As the days went on and media coverage mounted, public opinion swung decidedly behind the wreckers. One newspaper survey found that a resounding 91 percent of readers approved of their "free-lance rubble-rousers." ("Not only do I agree with their action, I think they should be reimbursed for their time," averred one reader. 55) The whole scene was getting out of control, and at length the city was forced to move. Five men were hauled off in handcuffs for wrecking without a permit and slapped with $100 fines, with Mayor Coleman Young denouncing them as "reckless vigilantes." Lest he look bad, Young hastened to add that the budget for the city's new fiscal year included 15 million dollars to fund "the largest demolition program in our history," which he thought would take down 3,000 structures. 56 As it happened, the brief jail time didn't have much of a deterrent effect on the opposition. "I'm so angry I could start tearing other houses down," 17-year-old Arthur Wirgau seethed. "And I'm going to." 57

Demolition had touched a nerve in Detroit. No one remembered this spontaneous outpouring of commonweal and chainsaw oil better than the city's next great wrecking impresario, Mayor Dennis Archer — he who gleefully cheered on the imploding Hudson's building. It was 1997, and Archer had been on a rampage, vowing to bulldoze every abandoned building in the city deemed too far gone for rehabilitation — as many as 8,922 of them — preferably in a single summer (the one before the mayor's November reelection vote, that is). 58 In a stroke of brilliance, Archer asked the federal Housing and Urban Development office to pony up the cash. Amid grumbling about ballot-count boosting, days before Archer's reelection HUD officials swept into town with some timely good news. "Secretary Andrew Cuomo granted Archer a campaign wish: a 60 million dollar loan guarantee, slated to finance the demolition of nearly every abandoned residential building in Detroit." HUD boasted that it would be the "largest such bulldozing ever undertaken by a U.S. city." 59 At the time, Detroit officials couldn't say how many structures would be razed, other than to hint that there would be plenty going down, in every voter precinct, for sure — as many as 10,000. For his part, Archer was on such an adrenaline high he could hardly see straight. "When you start talking about stadiums or even the 900 million dollars for the Chrysler plant, it doesn't touch or concern every citizen," he said after the HUD announcement, nearly shaking with emotion. "When you say you're going to tear down abandoned houses," he went on, "to be able to say you're going to start on it and tear them all down, I think creates an enormous pride in the entire city." 60 Archer's bulldozer hosannas struck some observers as pure pandering—"There's a 'Tear it down and they will come' mentality," one preservation officer complained. But as it turned out, the mayor had thornier problems to worry about than carping preservationists. "For more mundane reasons, Mayor Archer may miss his demolition deadline," a reporter wrote. "The city, which by law must award half of all its contracts to Detroit-based businesses, is expected to have trouble finding enough construction companies to do the job." 61

Despite decades of streamlining, wheel-greasing, and general head-butting, Detroit's demolition machinery was a shambles. Crowbar-toting citizens could wreak more havoc than the city could on a good day. Only months after Archer was returned to office, a comprehensive study called for "a complete overhaul of the city's demolition process," noting that the mayor's dream of razing 10,000 dangerous structures was pie in the sky given Detroit's "seriously fragmented" bureaucracy and "ineffective inter-department communication." You would sooner see bunny rabbits hopping around in demolition helmets than the city wrecking so many buildings at its dysfunctional pace. One citizen had been trying to get a vacant house torn down on her street near Eight Mile Road for a decade. In 1988 the city's building and safety engineering director acknowledged her request and confirmed that — yep — the structure was as wretchedly deserving of destruction as she had described it. Then it was officially green-lighted for demolition — in 1996. Two years later the house was still standing. The report finally recommended the drastic step of rolling the entire demolition process into one mega-agency to get rid of bureaucratic bobbling. Renewing his ardent appeal to the public, Mayor Archer was vowing to raze 3,655 houses in one year, but by late 1998 the city had yet to pay out any of the 60 million dollars HUD had given it for demolition, with editorialists concluding that "demolition isn't likely to outpace the rate of property abandonment in Detroit for years — if at all." 62

Fully three years later the city's wrecking woes were still a code-red crisis. Vacant structures were decried as festering havens for rapists, crack dealers, arsonists, and marauding packs of feral dogs, prompting one reporter to describe the distinguishing architectural style of Detroit as that of the "gigantic, fecal-stained doghouse." The hand-wringing and violin-playing grew so absurd it made Waiting for Godot look like a model of lucid good government. "Understandably, the city has difficulty keeping up with its demolition needs," the Detroit News lectured in an editorial. "Since the 1960s, the rate of abandonment in the city has outpaced the city's ability to take vacant and dangerous structures down." 63 Even though Detroit at the time razed five buildings per day — costs by then had gone up to $7,100 each — the number of vacant structures had stayed steady for years at about 12,000, and the fitful bouts of wrecking had "done little to shrink the city's swollen inventory of empty buildings near schools," a source of particular outrage after a spate of 10 schoolgirl rapes in late 1999, three of which were linked to derelict buildings. 64

As bulldozers munched picturesquely on a junked building in the background, Mayor Archer — never one to miss a photo-op where a toppling edifice might be squeezed into the frame — rolled out yet another plan in late 2000. With Shiva as my witness, he said, Detroit would raze 1,100 vacant buildings in five months, and bugger the city's neverending backlog of bombed-out properties. At the time, the Detroit City Council, which under city ordinance had to approve all building condemnations, reviewed at most 96 structures per week, a figure Detroit's Buildings and Safety Engineering Department was begging to have jacked up to 252 to help bring the problem under control. As Deputy Mayor Freman Hendrix groused, the Department of Public Works, which was feeding demolition orders to 16 contractors, didn't have enough orders from the council to keep the companies hopping. 65 The city administration suggested that the council hold hearings only on properties where a demolition was being challenged; the council refused, but eventually began whipping through an average of 150 cases in its Monday sessions, and cranked out as many as 250 in a single day. 66 (Later, the city would even roll out "blight court," a streamlined administrative tribunal giving officers power to remedy building code violations by such tactics as attaching wages and bank accounts, staffed by three full-time hearing officers. 67) By that time, Archer informed the electorate that 43 million dollars of the 60 million dollar HUD loan had wrecked 6,211 buildings since 1998, and he vowed to use the balance for more demolitions until October 2001. 68 All across the city, the blitz was under way, with the most dangerous abandoned buildings now tagged with a big yellow "D" for demolition. But there were still other snafus. Those "D"-marked buildings, as it happened, were not on a list to be boarded up by city workers. Why? "If they were boarded up, they wouldn't qualify as dangerous, and couldn't be demolished," said the city's interim public works director. "So for years the buildings sit open, where squatters and drug addicts take over." 69 And the violins played on. "The more they tear down, the more become abandoned," said one Detroit school principal. "Are we making any headway here?" 70

The Perils of Detroit, Scene III, Act 1,652: exeunt Dennis Archer and bulldozer entourage, enter Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick. In early 2002 Kilpatrick's administration hit the ground running with yet another "emergency citywide cleanup program" and yet more press releases vowing to take down 5,000 of Detroit's vacant buildings by that fall. In that budget year alone Detroit earmarked 13.2 million dollars for demolitions. 71 But just as the curtain went up — foiled again! By March the city had run out of cash for its wrecking program, and was scrounging around for private contributions for the effort, with the city's demolition firms flat out of luck. "The bottom line was, 'Ain't no more money, you'll have to wait,'" said Deb Taitt of Smash Wrecking Inc., as the city was pondering slashing its demolition contractor base from 20 firms to ten. One bright spot finally appeared on the dismal horizon in the form of 70-year-old asphalt magnate turned urban booster Robert Thompson, who in 2003 gave the city ten million dollars to get the wrecking back on track. The cash — doled out in one million dollar yearly installments — was expected to spring for up to 1,400 demolitions. Mayor Kilpatrick, at a news conference in the back yard of an abandoned drug haven that was shortly razed to the cheers of neighbors, mumbled a familiar refrain about how the gift would "create a huge dent" in the number of homes needing to be knocked down. 72 The scene, however, was not without a bit of Sturm und Drang. "As a backhoe crashed through the hovel's roof, unleashing a vile odor, onlookers called out: 'Oh!' 'Pray!' 'Good night!'," said a report. "Only one person seemed disappointed, a woman who disappeared after running toward the doomed structure yelling, 'That's my ... house!'" 73

As for the coda to this passion play, Detroit's political and business honchos are rushing pell-mell "to remove or renovate about a dozen of downtown's most blighted and dangerous buildings in time for the 2006 Super Bowl." The pre-kickoff festivities included a $700,000 low-interest loan to tear down the vacant Madison-Lenox Hotel (a busted-windowed, cinder-blocked "eyesore" just two blocks from Ford Field, the Super Bowl site). And other nearby towers were being pondered for removal, including the 25-story Statler-Hilton Hotel, which had sat vacant for more than 20 years (it was still decked out in awnings unfurled for delegates of the 1980 Republican National Convention). Officials said the structure could cost five million dollars to safely dismantle. "If a viable plan can't be developed, they need to come down," said George Jackson, who headed the quasi-public Detroit Economic Growth Corp. "We need to move forward and show our best face to the rest of the world." 74

Urban historian Camilo José Vergara has obsessively chronicled America's corroding inner cities for more than 30 years, and he has a few ideas about what sort of "best face" Detroit might think about putting on for posterity. Whatever the neighbors might say, Vergara thinks blight has its own kind of beauty. "I became so attached to derelict buildings," he once wrote, "that sadness came not from seeing them overgrown and deteriorating — this often rendered them more picturesque — but from their sudden and violent destruction, which often left a big gap in the urban fabric." 75 Demolition, he said, left us bereft of the past, however bitter and unlovely it might seem. Vergara had an idea, a riff on planned shrinkage, but without the wrecking. "I propose that as a tonic for our imagination, as a call for renewal, as a place within our national memory," he wrote, "a dozen city blocks of pre-Depression skyscrapers be stabilized and left standing as ruins: an American Acropolis." 76 Of course the very thought was repulsive to forward-moving city boosters and football fanatics, who would have dismissed it out of hand. But the prospect of pulling down those long-vacant Detroit hotels made others cringe as well. "The skyscraper, from a biblical perspective, may be as much an act of pride as the Tower of Babel," an Episcopal theologian, Bill Kellerman, commented. "They are huge projections, they have a life and history, they may even be synonymous with idolatry. If they level those skyscrapers, I can imagine the huge psychic toll that it would take on the city." 77

Detroit has been dubbed "the Capital of the Twentieth Century" for its pioneering embrace of the not always so savory future. What bold vision, asked Vergara, would the 21st-century city embrace? So far, he said, "most of the city center has been 'saved' by the lack of funds for demolition" 78 — a cost estimated to be in the neighborhood of 200 million dollars to toast all of Detroit's troubled and vacant downtown buildings. So put the cash toward wrecking the really vile doghouses. The future of the shrinking American metropolis, said Vergara, downtown Detroit, would look something like this. Place a moratorium on the razing of skyscrapers, "our most sublime ruins." Then, to shore up the structures and avoid accidents from falling fragments, the entire urban core of nearly 100 troubled buildings could be transformed into "a grand national historic park of play and wonder, an urban Monument Valley." 79 Roaming through this wonderland on Detroit's People Mover, visitors would be confronted with a sublime vista: "Midwestern prairie would be allowed to invade from the north. Trees, vines, and wildflowers would grow on roofs and out of windows; goats and wild animals — squirrels, possum, bats, owls, ravens, snakes, and insects — would live in the empty behemoths, adding their calls, hoots, and screeches to the smell of rotten leaves and animal droppings." 80

It was a beautiful dream. The half-ruined city, the American Acropolis. But in Detroit, as in America, demolition has long been more than a matter of public safety. It's a pragmatic philosophy, a whole state of mind. "Survival is more a matter of forgetting than remembering," mused Dan Hoffman, the architect, about the city's wrecking travails. The images of bulldozed buildings and imploding skyscrapers are powerful totems of our incurable romance with the new. Doggedly pursuing next year's model is, after all, the American way, Hoffman said. "There is no future in the past."" 81

1 Ron French, “Razing Paves Way for Renewal,” The Detroit News and Free Press,<./i>, 25 October 1998.

2 Kristin Palm, “One Building’s Struggle,” Metropolis, June 1998, 39.

3 Nadine M. Post, “Record-Breaking Implosion Unprecedented in Complexity,” Engineering News-Record 2 November 1998, 19.

4 Nadine M. Post, “Record-Breaking Implosion Unprecedented in Complexity,” Engineering News-Record, 2 November 1998, 19.

5 Judy DeHaven, “Today, We Say Goodbye to Years of Frustration,” The Detroit News and Free Press, 25 October 1998.

6 Lisa Jackson and Mark Puls, “Partygoers Revel as Building Drops,” The Detroit News and Free Press, 25 October 1998.

7 “People Mover Will Remain Closed Longer Than Expected,” Associated Press, 27 October 1998.

8 Ron French, “Razing Paves Way for Renewal,” The Detroit News and Free Press, 25 October 1998.

9 Wayne Woolley, “Nostalgia Lures Crowd to Experience Drama,” The Detroit News and Free Press, 25 October 1998.

10 Santiago Esparza, “Dust Clouds Swallow Downtown,” The Detroit News and Free Press, 25 October 1998.

11 Blair J. McGowan, letter to the editor, The Detroit News, 6 November 1998.

12 Janet Naylor, “Few Invited to See Hudson’s Blow Out,” The Detroit News, 15 October 1998.

13 Kevin Lynch, “Hudson’s Implosion Dust Safe, Tests Find,” The Detroit News, 30 October 1998.

14 Jennifer Dixon, “State to Probe Implosion for Safety of Workers,” The Detroit News and Free Press, 31 October 1998.

15 Jennifer Dixon, “State to Probe Implosion for Safety of Workers,” The Detroit News and Free Press, 31 October 1998.

16 Martha A. Churchill, “TV Slant on Implosion Plays to Hysteria,” The Detroit News, 3 November 1998.

17 Janet Naylor, “Hudson’s Rubble Turns to Charities’ Treasure,” The Detroit News, 4 November 1998.

18 Gregory D. Watson, letter to the editor, The Detroit News, 29 October 1998.

19 Iver Peterson, “Downtown Detroit Shops for a Future, but Not at Once-Grand Hudson’s,” New York Times, 23 December 1979.

20 Dan Hoffman, “Erasing Detroit,” in Architecture Studio: Cranbrook Academy of Art, 1986-1993, 28.

21 See Allen C. Goodman, “Detroit Housing Rebound Needs Safe Streets, Good Schools,” The Detroit News, 10 March 2004.

22Stalking Detroit, eds. Georgia Daskalakis, Charles Waldheim, and Jason Young, 14.

23 Jeff Long, Patrick T. Reardon, and Blair Kamin, “A Squandered Heritage: The Alternatives,” Chicago Tribune, 15 January 2003.

24 Cameron McWhirter and Darren A. Nichols, “City Council’s Blunders Speed Detroit’s Decline,” The Detroit News, 28 October 2001.

25 Cameron McWhirter, “Wrecking Homes Standard Practice,” The Detroit News, 19 June 2001.

26 Jodi Wilgoren, “Shrinking, Detroit Faces Fiscal Nightmare,” New York Times, 2 February 2005.

27 Cameron McWhirter, “3-Day Arson Spree Hurt City’s Image,” The Detroit News, 20 June 2001.

28 “Detroit Mayor Dennis W. Archer Thanks Thousands for Their Help In Shaping a Successful Angels’ Night Career,” City of Detroit press release, 2 November 2001.

29 Charles Waldheim and Marili Santos-Munné, “Decamping Detroit,” in Stalking Detroit, eds. Georgia Daskalakis, Charles Waldheim, and Jason Young, 107.

30 Dennis Byrne, “Downsizing Cities Has an Up Side,” Chicago Sun-Times, 4 May 1993.

31 David Usborne, “Motor City Fights Against Fulfilling a Death Wish,” The Independent (London), 31 May 1993.

32 Nancy Costello, “Detroit Official Proposes Turning Blighted Neighborhoods Into Pastures,” Associated Press, 5 May 1993.

33 “Day of the Bulldozer,” The Economist, 8 May 1993, 33.

34 “Clearance Sale for Detroit?”, Detroit News, 30 April 1993.

35 Nancy Costello, “Detroit Official Proposes Turning Blighted Neighborhoods Into Pastures,” Associated Press, 5 May 1993.

36 Kim Trent, “Official’s Plan Would Put Detroit’s Slums Out to Pasture,” The Detroit News, 27 April 1993.

37 David Usborne, “Motor City Fights Against Fulfilling a Death Wish,” The Independent (London), 31 May 1993.

38 Scott Bowles, “Some Rooted in Decaying Blocks Vow They’ll Stay,” The Detroit News, 30 April 1993.

39 Michael Betzold, “Vacant Lots Cast Blight on Neighborhoods,” Detroit Free Press, 13 August 1990.

40 Detroit City Planning Commission, “Survey and Recommendations Regarding Vacant Land in the City,” 24 August 1990.

41 Charles Waldheim and Marili Santos-Munné, “Decamping Detroit,” in Stalking Detroit, eds. Georgia Daskalakis, Charles Waldheim, and Jason Young, 105.

42 Joseph P. Fried, “City’s Housing Administrator Proposes ‘Planned Shrinkage’ of Some Slums,” New York Times, 3 February 1976.

43 Roger Starr, “Making New York Smaller,” The New York Times Magazine, 14 November 1976, p. 105.

44 Ibid.

45 Witold Rybczynski, “The Zero-Density Neighborhood,” Detroit Free Press Sunday Magazine, 29 October 1995, 17.

46 Kate Stohr, “Shrinking City Syndrome,” New York Times, 5 February 2004.

47 Patricia Montemurri, Zachare Ball, and Roger Chesley, “15,215 Buildings Stand Empty,” Detroit Free Press, 9 July 1989.

48 “Introduction: Committee Work,” Stalking Detroit, eds. Georgia Daskalakis, Charles Waldheim, and Jason Young, 13.

49 Peter Gavrilovich, “Rubble Sits...And Sits...And Sits...,” Detroit Free Press, 13 July 1989.

50 Zachare Ball and Dori J. Maynard, “Neighborhood ‘House-Busters’ Strike Again,” Detroit Free Press, 2 July 1989.

51 Mike Williams, “Neighbors Keep Up Demolition,” Detroit Free Press, 3 July 1989.

52 Anne Kim, “Fists Fly as House Debris Blocks Chatham,” Detroit Free Press, 7 July 1989.

53 Michael Betzold, “Don’t Do It Yourself, Demolition Expert Says,” Detroit Free Press, 4 July 1989.

54 Constance Prater, “Have Patience With Vacant Houses, Council Pleads,” Detroit Free Press, 6 July 1989.

55 “Soundoff: Should Residents Tear Down Abandoned Dwellings?,” Detroit Free Press, 4 July 1989.

56 Anne Kim, “City Gets Tough on House-Busting Neighbors,” Detroit Free Press, 8 July 1989.

57 Anne Kim, “House-Busters Say They Feel No Regrets, May Wreck Again,” Detroit Free Press, 9 July 1989.

58 Darci McConnell, “Council Suspects Politics is Driving Demolition Plan,” Detroit Free Press, 21 October 1997; Robert Ankeny, “Archer Seeks $50M to Raze Buildings,” Crain’s Detroit Business, 1 September 1997.

59 Alyssa Katz, “Dismantling the Motor City,” Metropolis, June 1998, 33.

60 Jennifer Dixon and Darci McConnell, “HUD Hands Detroit a $160-Million Gift Days Before Election,” Detroit Free Press, 29 October 1997.

61 Alyssa Katz, “Dismantling the Motor City,” Metropolis, June 1998, 37.

62 “Demolishing the City,” editorial, The Detroit News, 11 November 1998.

63 “Abandoned Housing Misery,” editorial in The Detroit News, 24 September 2000.

64 Cameron McWhirter and Brian Harmon, “Derelict Buildings Haunt School, Kids,” The Detroit News, 24 September 2000.

65 Cameron McWhirter, “Detroit Seeks to Increase Condemnations,” The Detroit News, 2 November 2000.

66 Cameron McWhirter and Darren A. Nichols, “City Council’s Blunders Speed Detroit’s Decline,” The Detroit News, 28 October 2001.

67 Sarah Karush, “Detroit Gets New Weapon Against Urban Decay: Blight Court,” Associated Press, 30 December 2004.

68 Cameron McWhirter, “Detroit Destroys Vacant Buildings,” The Detroit News, 1 November 2000.

69 Cameron McWhirter, “Bureaucracy Chokes Detroit,” The Detroit News, 29 October 2001.

70 Jodi S. Cohen, “Schools Ignore Vacant Houses,” The Detroit News, 25 November 2001.

71 Cameron McWhirter and Darci McConnell, “Kilpatrick Gets Ready to Start Demolitions,” The Detroit News, 29 January 2002.

72 Darren A. Nichols, “$10 Million Gift to Raze Detroit Eyesores,” The Detroit News, 7 May 2003.

73 M.L. Elrick, “Big Donor’s $10 Million Will Raze City’s Eyesores,” Detroit Free Press, 7 May 2003.

74 R.J. King, “Detroit’s Eyesores Slated for Cleanup,” The Detroit News, 9 August 2002.

75 Camilo José Vergara, American Ruins, 23.

76 Camilo José Vergara, “Downtown Detroit,” Metropolis, April 1995, 33.

77 Camilo José Vergara, “Downtown Detroit,” Metropolis, April 1995, 35.

78 Camilo José Vergara, “Downtown Detroit,” Metropolis, April 1995, 36.

79 Camilo José Vergara, “Downtown Detroit,” Metropolis, April 1995, 36.

80 Camilo José Vergara, “Downtown Detroit,” Metropolis, April 1995, 37.

81 Dan Hoffman, “The Best the World Has to Offer,” in Stalking Detroit, eds. Georgia Daskalakis, Charles Waldheim, and Jason Young, 43.

Reprinted from Rubble, by Jeff Byles © Jeff Byles. Published by arrangement with Random House.

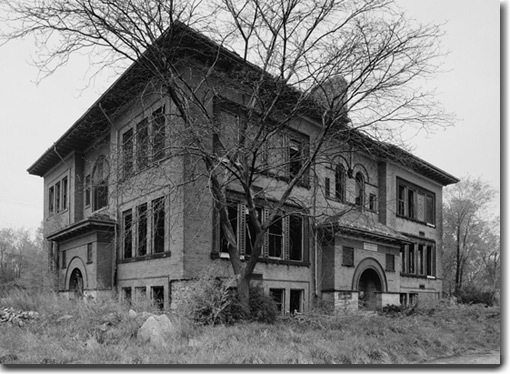

Photographs: Preston School, 1251 Seventeenth Street, between Fort & Porter Streets, Detroit, Wayne County, MI. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Buildings Survey, Reproduction Numbers HABS MICH,82-DETRO,62-8 and HABS MICH,82-DETRO,62-9.

This article originally appeared in Issue 2, January 2006.

===================================================================================================

|

|