| 2010 SUMMER EDITION – NO. 38 |

Aileron

In the warm, thinning light of summer evenings in Colorado, I knew where to find my father. Once our supper table was cleared and I'd dust panned the crumbs away, I reached for the kitchen door knob.

We lived far out in the country beyond a bend in the road in a small ranch house painted soft lavender, the color my mother loved. It was a place of virtues for me, a wandering child of ten prone to loneliness and reverie. A wild weedy field full of dragonflies wrapped around the side of the house, and, along the front yard, a row of giant climbing trees dipped their arms low enough for my hands. But at twilight, when chiggers and mosquitoes forced me indoors, I sought out my father's domain, our two-car garage.

Daddy's VW Bug, painted sky blue, greeted me as I swung the door wide. Not two feet away sat Mama's finned white Fury, both cars side by side, the way my parents would be throughout life, an inseparable fleet of two. Despite this, I believed my father belonged to me. I was most like him, taking after his side of the family: my blondish hair a whisper of his mother's; my nose and eyes a regeneration of his aunt Malta; and my middle name, Ray, his.

I pushed open the screen door and, for a moment, paused, dizzied by the pungency of warm engine oil, gasoline and treaded rubber. A funnel of soft light fell through the only window, and there, half perched on a stool, my father curved like a fishing pole over his work bench, casting and dropping his fingers into a pool of parts and bits that seemed from another world: model-pins, Xacto blades, ball-headed studs, swivel socket links, stabilizers. Dust motes swirled around his dark thatch of hair, curling upward to the ceiling where a flock of delicate model airplane skeletons dangled from the rafters, covered in sleek flawless skins of brushed reds and buttery yellows. Though meant to float on the air like prairie birds, Dad's airplanes, with their tissued wings and opaque membranes, appeared more to me like pterosaurs: mysterious, primal creatures taking shelter in our garage.

Though I didn't recognize it then, I sensed my father's awe. Aviation was yet a youthful and evolving dream in 1962 with nearly a decade to go before Boeing would fly its first 747, ferrying crowds of people across unfathomable miles as easily and comfortably as Chevrolets. Nearly as many years would pass before Neil Armstrong scuffled his boot in the dust of the moon. Flight and its mystery was imaginative and visionary, and in the case of missiles and booster rockets, heroic and powerful.

My father didn't look up. I stood for another small moment, the door half open, and inhaled a deep whiff of glue and wood dust, my lungs billowing and folding like bellows. In the next half second, a clattering sound exploded behind me from the back corridors of the house. Quickly, I pulled the door shut as the noise tumbled up against its hollow core, muffled and fierce. In a distant bedroom, my little brother Roddy's fists and heels whirled and pounded, bits of gears and toy parts scattering and crunching under his heels. The fury of his barkings gave way suddenly to the deep thumping sound of his forehead, deliberate and unhurried, banging the wall.

Bong, bong, bong.

My mother's footsteps hurried through the distant hallway as her voice rose and sank. Dad's face lifted to the window, his hand stilled midair, a tube of epoxy balanced on his fingers. I knew he was waiting, listening like me, and my older sister Becky Ann in some other part of the house, her bedroom maybe, holding her palomino mare and the big chestnut stallion still on the pasture of her bedspread. Each of us paused, stalled in our trajectories long enough to measure whether the evening could go on.

I carried only one word for my brother, then. Retarded. Other words would rise as I came of age, obscure terms I didn't understand, and half my lifetime would pass before autism fledged fully in the world. What I knew then, I'd known forever: my brother was a shy boy with a funny, flat-footed run and a loppy smile, and what was wrong with him had moved into our home like a seizure, unpredictable and baffling, thinning my mother's smile into a red-lipped line, rimming her hazel eyes with tears and bowing her head in prayer. I couldn't remember what my life or my family had been before.

A silence fell, a dense lack of sound. After another moment, the silvery tube in my father's hand resumed its journey downward, delivering to the waiting dihedral of his wing, a bead of glue. Pushing out a puff of air, I shifted my weight away from the door and slapped my flip flops down two steps to the concrete floor. Dodging the VW's fender and sidestepping the lawn mower, I came up to my father's side. He tugged a tall stool out from under the table and held it steady as I climbed on. Then, he chose for me a grainy square of sandpaper and a slender piece of soft white wood.

Balsa was an essence to me: a silky slide beneath my thumb and forefinger, a tangy citrus inside my nose. Its delicate airy thinness, when trimmed and deburred, could catch the edge of the wind and wing to the sky. I was finally old enough to build my own plane, and the piece my father handed me was not just any scrap, but my first wing, with a trailing edge and elliptical curve that could part and shape the air.

"Easy there," he advised.

I halted, mid-stroke, the heat from my vigorous sanding wafting up from the wood.

"But Daddy, you said it's supposed to be thin," I protested, my voice reedy and high. I was an impatient learner with a penchant for perfection, and the tyranny of my expectations made me anxious and accusatory.

"Well, you're right there."

He paused, measured and unaffected by my distress, an approach that would both toughen and alienate me at different points in my life. I waited, jiggling my knee as he finished fastening a miniscule wire inside his fuselage.

At last, he straightened, satisfied with his handiwork, and turned to me.

"Can't flatten that wing, though," he observed. "It won't fly."

Taking up a pencil, he sketched a few strokes on the white paper surface of the table. Quick and clean, in a draftsman's hand, a wing appeared. Cutaway from the side, its elegant swell on the left edge spilled down to the right, sloping and vanishing into a mica-thin trailing edge. Three more pencil strokes and the wind arrived, slipping over and under the wing. He stretched his long arms up above the storage cabinet and brought down a wing in progress, shifting it in the light so I could peer down its length and register its curve. Then, he propped it in front of me and turned back to his fuselage.

It was the beginning of my long journey toward acquiring patience and the beauty of fine skills, neither of which came easy to me or without struggle. As it was, my plane slowly came to life and, by summer's end, I was in the Volkswagen alongside my father on the way to a model airplane contest on the flat plains of Colorado Springs.

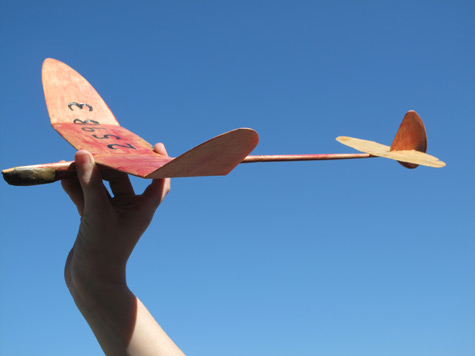

Feather light and weighing less than a gram, my hand-launch glider rested in my lap, its pencil-thin fuselage like a glass straw in my fingers, its stabilizer barely thicker than a shaving. If not for the spotty brushes of red paint covering its surface and trembly black numbers I'd painted across the left wing, I wouldn't have believed it was there. Unlike Dad's plane, mine hadn't a hefty engine, or even a contraption for a catapult launch; it was too simple even for ailerons, the little movable flaps on wings that turn a plane into an acrobat.

"How do you say that again?" I'd asked a few weeks ago, deflated to learn my plane was too young for loops and flips. Daddy stopped tamping down his tobacco.

"Ay-ee-le-ron," he repeated, holding his pipe a few inches from his mouth. He cleared his throat. "Tricky word. It's French, I believe."

"What's it mean?"

"'Little wing', I reckon."

Hearing this, my head felt lighter. I caught the word out of the air and gave it to my plane, knowing she would need all the cleverness and French she could get. If my Little Wing were to have had any hope of climbing into the sky it would come partly from luck, and partly from the strength in my arm and angle of my wrist as I flung her upward. Once airborne, she'd be on her own, up to the fate of fancier forces I didn't fully understand — downwash, drag, wake turbulence — all of which meant she'd either spiral upward, catch the wind and glide slowly back to earth, or cut a half slice through the air, stall for a miserable moment, and plummet straight down as if shot out of the sky.

Daddy pulled the VW into a dirt lot next to a crowd of other cars and we got out into a vast empty field. The sweep of space rushing all the way to the horizon made me teeter for a moment and I stood pressed up against the car while Daddy unloaded our tent and cooler. Holding my plane, I didn't move until he called me to come on. Cars were pulling in all around us with trunks swinging open and car doors slamming. Boys tumbled out and followed their dads, toting tool boxes and radio control gear. Here and there, moms clipped alongside with plaid thermoses of iced tea and brownie-stuffed Tupperware. The air rustled with excitement and we were surrounded by a pageant of airplanes, all graceful and long-winged with sashes of black and red adorning the wing tips and rudders.

In the bright bald daylight, Little Wing looked blotchy and small. Waiting for Daddy to set up our tent I tucked her under my sweater and, once the tent was anchored, slipped her inside behind the cooler. Unknown to me, this was my pattern, a tendency to shield imperfection. For as long as life, whenever people stared at Roddy as if he were an animal, I had shifted my body in front of him. I did this now for Little Wing, stepping between her and the world's eyes, which I knew could penetrate and wither. In the shadows, she wouldn't have to feel shaky about who she was.

With her tucked away, I stepped back out into the sunshine and settled myself on the blanket next to the tool box. It's stepped layers hinged open to a treasure of doo-dads. Daddy sat in a webbed beach chair, fiddling with his remote controller, and I took up doing what I loved best, fishing out the parts and pieces he needed: a spool of thin wire, needle nose pliers, the red tipped cap to the glue. I felt safe there at his feet.

"Howdy there, Ray," a man hollered out, pulling up to our tent. He had a paunchy middle and a round balding head that looked pink and sore from the sun. "Heard my oldest boy has some competition today."

I looked up, shielding my eyes, squinting in the glare. A gangly boy with a head of dark wiry hair shuffled just behind the man to a big-footed halt. And buzzing lower down near the man's thighs was a younger boy, a Shorty-pants with a rooster cowlick that sprang from his head, like Roddy's. He was pitching a plastic toy plane from hand to hand, throttling the air with a whining engine noise and then plunging its nose in a low-flying death dive.

"Well you heard right, I reckon," my father said. He stood up from his folding chair, wiping 3-in-1 off his fingers, and held out his hand. Everyone knew my dad. He was a champion flyer and our rooms at home were lined with his gleaming, spired trophies. "This here's my daughter. I expect she'll give you a run for your money."

The man let out a delighted "Ha!", and his moustache split above his teeth as he grinned and shook hands with my dad. His eyebrows danced up and down and his pupils darted about, searching for my plane. Then he clapped a hand between his older boy's shoulder blades.

"Hear that, Buddy? There's a girl at your rudder!"

A small pulse of uncertainty penetrated my chest and lapped once around my ribcage. This was not a man my heart liked. His arm shot out and caught Shorty Pants in a neck hold, and he scrubbed the boy's hair with a knuckled hand as he snorted and caught my eye. He winked, the drop of his eyelid like a small, quick cut. Then he looked over at my dad.

"Believe you've got a boy too, don't you Ray?"

I dropped my chin to the tool box, where screws and bolts lay bunched in their bins. The air thickened suddenly in my ears and I felt something heavy pressed on my chest. Glancing sideways, I brushed my eyes across Daddy's face. A shadow flickered across his eyes.

"Yes sir," he said. "I do." His voice was not his own. Its color had shifted slightly, as if dampening down a shade. The man didn't notice.

"Still too young to come along, is he?"

The smallest of minutes passed. I thought of Roddy. If he were here, he wouldn't be bombing a toy plane. He'd be hunched beside me on the blanket, his little boy legs stretched out from his shorts, pale as parsnips. He'd be pulling on his lip, making his washing machine sounds like he does. Hissing at first, then a low chugging in his nose, tongue thrubbing far back in his throat, followed by a shush shush shushing and a whispery trail of rrrs, and finally, a whiney yi yi yi yi yi, meaning he'd come to the spin cycle, at last.

I picked up a bolt and turned it with sweaty fingers. Out of the corner of my eye, I glimpsed a rag in my father's hand wiping slowly down the leading edge of his wing, then his fingertips running back over the same edge, as if he were checking for splinters. I wondered, if I could see inside his head, what would be there? Would it be crowded like mine, tangled with all the things you couldn't say?

"That's right," he said, finally.

When my father spoke again, he remarked on what a good day it was for flying. Then the boy's father said, "May the best man win," and they all turned away.

I watched them go, the man's arm draped over the taller boy's shoulders, Shorty Pants running backwards in choppy steps and jabbing his toy plane in the air as they disappeared into the sea of tents. In their wake, a voice rose from some deep place within me and broke the surface of what I feared.

Daddy doesn't have a real son. I gasped and jerked my eyes to my father's face, to see if he'd said this. I knew he hadn't. I got up and went into the tent, sat down in the shadows next to my plane and wrapped my knees in my arms. My head, wobbly and heavy, lay like a stone on the knobs of my kneecaps. I couldn't say how long I stayed there, feeling a murky and shapeless regret at who I couldn't be. When I heard Daddy calling me to fetch my plane and come on out from the tent, I stood up, knowing I was different. No matter how well I threw or how lucky I got with the wind, I would never be a boy. And nothing I could do would ever fill that space for my father.

When I stepped squinting into the sunlight, my dad was shaking hands with a man holding a stop watch, and I knew it was my turn to fly.

"Aren't you going to time me, Daddy?" I whispered up into his ear.

"No. No, that wouldn't be right," he said, matter-of-factly. "It has to be official. Go on with Mr. Smull here. He'll record your time."

I moved off our blanket as if stepping into the deep. My courage slid like water down my legs.

Mr. Smull explained I'd have three tries. To my dismay, the three would not be done all at once, but with an hour break between. This was in favor of fairness, mixing up the breezes and elements like a deck of cards so that no one had an unfair advantage. But for me, whose heart had slipped away moments ago and who wished now for a hasty finish, it only served to make me miserable.

Mr. Smull may have sensed my distress. He was soft-spoken and kind as he led me beyond the tents to a marked off space in the dirt, and repeated the rules to me before walking a few paces away and holding up his stop watch.

"Okay," he said. "Give it a whirl."

I turned Little Wing onto her side and placed the pad of my forefinger in the notch Daddy had carved in her wing right next to the fuselage. My other fingers slid down to the blob of clay that protected her nose, and squeezed. Looking out over the field I took a deep breath, and then another. Finally, knowing I couldn't wait any longer, I jumped into a sideways slide and whipped my arm in a low scoop, as if flinging a rock across water, winging the plane off my fingers.

Little Wing spun upward and vanished into the glare of the sun. I huffed and closed my eyes, hunching up my shoulders. I didn't want to see her drop like a stone and already I could feel a sting of tears under my lids. Mr. Smull said nothing, and I guessed he was feeling bad for me. When finally I glanced over, he was standing still, stopwatch held out in front of his white collared shirt, looking up.

I frowned and lifted one hand up to shade my eyes, tilting my head back. High overhead, Little Wing hovered in the same spot, caught for a moment in a gust of air that pushed directly on her nose. Then just as suddenly she sighed and slid forward, floating for several yards before dipping slightly and gliding for several more, then lifting gently and bobbing, as if I'd taught her how to dance. Unhurried, she circled and floated the way she was supposed to, and just when I thought she was coming down for a landing, she lifted her nose one last time and skimmed along the cheat grass another two yards before a tuft reached up and caught her, bringing her to rest.

Mr. Smull clicked his watch and wrote down a number, which, by day's end, landed me a second place trophy.

If I were my best friend Lizzie, or any other child with a passel of siblings, noisy and normal, I could have celebrated. I'd have held my trophy and paraded it to the car, tracing its wooden spire and flashy golden wings, exuberant and chattering. I'd have insisted Daddy swing into the A&W on the way home so I could order a strawberry shake and French fries, even though it was getting dark and Mama had a pot roast warming in the stove.

But there were so many reasons not to. How could I win, when Roddy couldn't? And, most importantly, how could I not be me, a child who knew a trophy could not fix my family?

Instead, I rode home quietly, holding little Wing in my lap, not asking for more. I didn't yet know I wore the caution of a child growing up with a disabled sibling, who'd learned well the world could blindside you, especially in moments of extraordinary joy. My heart already told me it was safer to lessen those moments and bring them to a close. If I didn't rejoice then no one could take them from me. And no one could shoot me down out of the sky.

Riding along in my lap, her nose scuffed and her fuselage cracked, Little Wing likely knew what would, in the end, prove true. I wouldn't go on to be a champion flier. Beyond that day, I abandoned her to my father's workbench. Nearly 40 years would pass before I gathered enough wisdom not to feel this as a failure. Only recently, would a deeper truth come to me, unexpected and unbidden, on a bright winter day in the year 2009. Happily mussed and dirty, I was in the kitchen of my new home in the Pacific Northwest doing an ordinary thing — sorting through a stack of books on the kitchen table — when I spotted an oddly made box tucked back in the closet. I'd forgotten it was there.

Slender and upright, the box itself was a marvel of craftsmanship and engineering, its custom cut panels fit together in a seamless concert of cardboard and packing tape. It must have taken my father an entire evening to fashion it for me.

Curling my fingers around the handle, an arching twist of duct tape, I lifted. The box floated to the table top, feather-light, as if bearing thin air. Laying it gently on its side, I reached for the Xacto knife and carefully razored away the packing seal, the cardboard lid and six stitches of scotch tape binding the bulges of bubble wrap inside.

Part by part, Little Wing emerged. First, her stabilizer with its shredded edge; her fuselage, its dark wound soldered beneath a knob of aging glue; and her wings: the right, and then the left, black lettering, wobbly and brave, marching down the center surface.

Magically and improbably, here she was in my hands, light as breath. All these years, my father had kept her like an heirloom. Through the '70s and '80s, she survived the unraveling of the missile defense program, the massive layoffs of engineers, job hopping with my father from Colorado to Florida to Virginia and back to Florida. Each time he found a new job and, along with Roddy and my mother, set up a new home, my father chose a corner for his workbench and mounted, on the wall, his finest models. There, among his beauties, he always hung my scruffy little plane.

Now, I lifted her to the gray light of the window, turning her like delicate and ancient wonderment. She twirled like a dancer, an acrobat, as if winged with ailerons. The air stirred, and the late summer light of my childhood, the heat of the garage, the pinging of moth wings off the garage window entered my kitchen. Around me breathed the warm perfume of oil and tires, the ticking of the Volkswagen engine. As I touched her wing to my nose, I inhaled a soft citrusy fragrance. Balsa.

It came to me then, her meaning in my life. What drew me to my father's work bench all of those evenings was neither ambition nor trophies. I simply needed to be with him. To feel his steadiness in a home rocked by affliction, the gentle and precise way he brought the plane to life, the comfort of minute sounds, and the sanctuary of being inside a moment, shaping something beautiful with my hands.

What I couldn't understand as a child, I felt now. In the stillness of our garage, I was piecing together more than an airplane. I was assembling what would carry me through the rest of my life: a private peace. As the wind slid from the mountains and the earth turned quietly toward dusk, I learned it was possible to control the random elements of a tumultuous world, with only me and Daddy, the fusty smell of glue and sawdust, and the rising curve of a slender wing.

Photo courtesy Margaret Combs.

BACK TO TOP

===========================================================================================

|

|