LOST THING  |

APRIL 2009 – NO. 32 |

|

|

After the Boat Went Down

J. Walter Elliott took three doses of quinine that the Sisters of Charity had given him on the boat, all at once. It was a futile gesture, but it was all he had at the time. Elliott, an army captain from southern Indiana, lay shivering on a cypress log, snagged in drift on the Arkansas side of the river. He was so exhausted that for a while he could not sit up. He was tormented by mosquitoes. In the darkness nearby, he heard a young man gurgling and moaning. The young man seemed to be losing his hold on a flooded tree.

Elliott listened to the gurgling and moaning for hours, and not long after the source was revealed by the faint light of dawn, the young man died. By then, rescue boats were slowly pirouetting on whirlpools in the open channel, and he noticed another man a little farther away, fully out of the water, clinging to another flooded sapling, his grasp weakening, too. The man inched lower and lower until his head slipped beneath the muddy water, then unexpectedly broke the surface again, clawing at the trunk and pulling himself up, though not quite as high as before. The scene kept repeating, stuck in frustrating denouement. The man went under; the man came up; the man went under again. Elliott could not get to him because he could not swim.

When he was finally able to stand, Elliott focused his attention on a nearly naked man who lay at his feet on a thin, sodden mattress. The man was shivering uncontrollably, as everyone was. The shakes could represent the insistent quivering of life or the final shuddering of death. All of them had engaged in mortal parlay many times before, had felt their hearts in their throats at Perryville and Stones River and Chickamauga, had lain sleepless at night in the purgatory of the prisons, watching their breath fade out before them in the cold. They had been sick, wounded, or both. They had been close to giving up and could have done so in a single breath. Each time, when they thought they had endured the worst, it had reappeared ahead of them, but each time, when they thought they had reached the end, it had been delayed.

Elliott had feared death both on the burning boat and in the river, but he was still there, rhythmically striking the nearly naked man with a switch. He was intent on keeping the man alive, and pain was the only tool at his disposal. The man, whom he did not know, feebly begged him to stop. There were others nearby, and soon the bodies of two men and of a young woman lay at Elliott’s feet, evidence of his failures. Up and down the river he saw men clinging to flooded trees, which bowed under their weight and in the tug of the currents. Some clung with death grips; others hung limply like snagged debris. For miles down the river, he could see people floating away lifelessly or barely alive, on driftwood and pieces of the boat. Somewhere among them was Romulus Tolbert, a private, also from southern Indiana, who grasped a board or a piece of driftwood (the detail would be lost in the telling). Tolbert had lost sight of his boyhood friend John Maddox, a fellow private, who until then had been with him nearly every step of the way. Tolbert and Maddox had served together in the local militia back in Indiana, had endured enemy fire and wearying marches through Georgia, and had survived the squalid Confederate prison in Alabama before boarding the Sultana on their way home.

Private Perry Summerville, who grew up not far from Elliott, Tolbert, and Maddox in rural Indiana, and had also been in the Alabama pen, was now miles downstream, carried helplessly on the unyielding currents, floating toward Memphis between two wooden boards, one clutched between his shriveled, aching hands, the other hooked under his feet. Another refugee from the Alabama pen, George Robinson, a private from Michigan, was already beyond the city, floating senselessly on a dead mule amid bobbing barrels, discarded clothes, deathly quiet bodies, and smoldering splinters of the boat.

From his perch on the log, Elliott watched men hanging over the sides of the distant boats, dragging survivors and bodies aboard. He heard voices echoing across the river, and here and there someone crying out deliriously or moaning so pitifully and interminably that it was a relief when the voices finally quieted and faded away. Men mimicked the calls of birds and the croaking of frogs, or sang favorite songs from childhood or the war: Come on, come on, come on, old man, and don’t be made a fool, by everyone you meet in camp, with "Mister, here’s your mule!" Beyond the man hanging on the tree Elliott saw a pirogue piloted by a misplaced Rebel soldier, nosing in and out among the trees. It was a curious sight. Elliott called out to him and pointed to the young man clinging to the tree, and the Rebel took his cue and saved him. In the distance, in a flooded field, he saw a group of men crouched together on the roof of a barn, hugging themselves against the chill, occasionally swatting stiffly at mosquitoes. It might have seemed strange, mosquitoes in the cold, raising welts amid the goose bumps, but there was no logic to anything now. The world and the mind played tricks.

He tried to commit every detail to memory. Years from now he would struggle to make sense of it all, to put it into words, to impose order, to impress anyone who was willing to listen. Nothing would be too preposterous to believe: The hapless man rolling over on a twirling barrel, like some macabre sideshow; the man who had tied a tourniquet around the ruptured, pulsing veins of his broken legs to keep from bleeding to death, who asked to be thrown overboard to drown rather than face being burned alive; the six or seven men clinging to the back of a terrified horse as it swam down the firelit channel; the sister who stood on the bow of the Sultana, attempting to calm the drowning masses until the moment the flames consumed her; the woman who drifted serenely through the mayhem, buoyant as a water lily in her hoopskirt, as if in a dream — which she may well have been. They would be characters in Elliott’s stock scenes. He would use them to populate his mythopoeic tale.

Other survivors would keep their memories to themselves. But even now, in the aftermath, all of them faced the same questions that had raced through Perry Summerville’s mind when he awoke, flying through the air above the darkened river: How did I get here, and what do I do now?

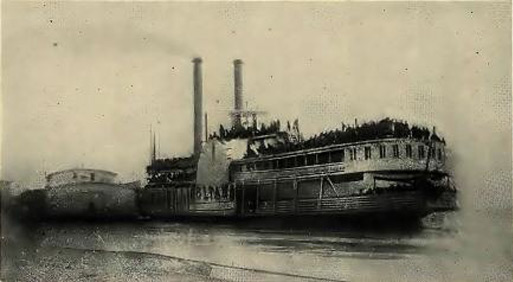

Excerpt and photo from Sultana: Surviving the Civil War, Prison, and the Worst Maritime Disaster in American History, published by Smithsonian Books/Harper Collins (2009).