FICTION  |

MARCH 2009 – NO. 31 |

|

|

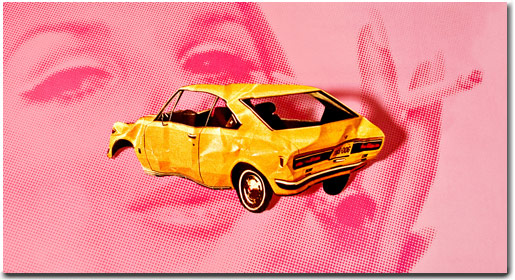

Scarecar

There were chocolate stains on his fingers, and he sucked them as he watched her. From his place on the wrecked car's floorboards he could see her move from the grill to the house, making hamburgers. She wore cut-off jeans and a halter top. Her legs were bare through the cut-offs. He knew that her name was Rachel, four years his senior. She seemed even older. If his parents stayed on at the new house for as long as they did at the last one, he would be at her school in five years. Petersville High: its facade looked like a prison when he saw it through the window of his parent's car. He couldn't imagine what it looked like on the inside. By the time he knew she would be gone.

The house belonged to her mother, Molly, who kept an eye patch over her left eye. Molly spent most of the daylight hours lying in bed. At least, this is what Rachel told his parents the once they knocked on Molly's door. Rachel told them Molly was resting, "She's having trouble with her back." She spoke with formality and explained that they could stop back anytime. On the short walk home, his parents wondered if the chronic trouble with Molly's back had anything to do with the smashed car in her backyard. A scarecar, his mother called it, her voice full of rue.

He wanted to explore it, play inside it, but his mother was firm. "It's not our yard," she said "If you ask Molly's permission, and she says it's alright, then it still wouldn't be alright."

His mother's words didn't matter. He felt as though the scarecar was his own, just sitting vacantly all day on a weedy jetty of Molly's yard. It seemed to be sleeping: lamps clouded over, grill bent upward, tires like deflated basketballs and the whole thing covered over in several seasons' worth of fallen leaves. The windshield was only half there and what was there was cracked. He wanted to trace the lines with his fingers, knowing it might cut them. The car had magical properties, he imagined, which would protect him.

Rachel took the last hamburger off the grill and closed the lid. She slung an arm through her cardigan on the way inside, balancing the platter. He didn't move, but watched her until she was all the way inside. He dug more ancient chocolate from the glove compartment.

He watched his mother string colored lights along the porch while his father laid carpet in the living room with a staple gun.

"How do you think she affords that place?" his father asked.

"Well," his mother said, "remember Rachel telling us that Molly worked for that mailing campaign? She must be licking envelopes all day. Forget her back .…"

His parents laughed a little. The day before he'd seen Molly stooped in her back yard, her back to his house, pulling weeds from around the car. His mother called to her and waved but Molly didn't seem to see her.

He listened to his father's staple gun plugging into the hardwood. He imagined what the staple gun would feel like in his hand. He could defend the whole house from invasion with such a beautiful weapon.

His mother hummed to herself as she strung lights along one end of the porch to the other. Faintly, from his position on the floor, he could hear his father humming a separate tune. At times they seemed to overlap, then they'd fade apart again.

When the lights switched on the porch felt like a room.

His first approach was stealthy, creeping silently up to the car and heaving himself over the unopened door, so as to cause as little noise as possible. But his aim was off, and his hands slid on the wet leaves, knocking his arm into the side-view mirror and landing him on the wet dirt. His mind raced with excuses for the bruise as he brushed himself off and tried for a second assault. From behind the wreck of a car, aligned with its caved trunk, he flung himself at it. He was in.

There were leaves strewn everywhere he could hear trees shaking. In the front seat on the floorboards were unopened cans of beer, cigarette butts, paperbacks.

The front seat was bare and worn. He climbed in and started spinning the broken wheel, stomping on the gas petal and muttering instructions to his comrades in the air. They were steering the car together, and veering it straight through the trees toward Molly's house.

The sound of raised voices snapped his dream away. Rachel's voice and what must have been Molly's carried through the trees. "You don't fucking know," he heard Rachel shout, and a slamming door. Blushing, not knowing why, he crept out of the car.

He didn't return to the inner-space of the scarecar for some time, but it stayed with him. For several weeks he courted it, keeping his distance. He imagined it was charging at him, invading his parent's place or simply lending him its consciousness, advising him with silence. He felt it moving when he lay in bed.

"I saw that Rachel today." He heard his mother in the kitchen, mixed in with the sound of stacking dishes. "She seems to be quite mature for her age."

No response from his father, drinking beer in the living room and watching one of his nature shows.

"You know, I was fixing the lights on the porch the other night and could have sworn I heard voices coming from that car."

"Voices?" his father said.

"In the scarecar."

"What car?"

"You know, the one that Molly crashed. The Pinto. I heard Rachel in there with a man last night."

"There was a man in there?"

"Well, a young man."

The sound of clattering increased as dishes were shifted from one shelf to another.

"You wonder why she leaves it there," his father said.

"Who?"

Molly."

"It's not bringing the property value up." His mother was louder.

"I'll talk to her. I'll say she should get rid of it."

"It's like having a pet die," his mother said, "and just leaving it there."

"I'll talk to her."

"Ok," his mother said.

When he stood in the scarecar's backseat, the woods were waves that parted in his wake. "Full ahead. And at my word, dive!" He felt the wind, a real wind. The car's prow cut into leaves. He knew this alone was the real thing; all other worlds were imitations. Molly's house loomed, rising high up.

"Prepare to fire!"

He didn't hear Rachel crunching the leaves behind him, green notebook in her hand, until she stood next to the car.

"What are you doing?"

He felt ashamed. "Nothing. Playing, I guess."

He faced forward. The game had disappeared. He wanted her to disappear.

"I can see that," she said. "What are you playing?"

He shrugged.

"You know you're not supposed to play here. This isn't really your yard."

He nodded, kept his head down.

"You know what Molly does to kids who play here in the car?" She moistened her lips.

"Not really."

"She wraps their hearts in newspaper, and lights them, and floats them way out on the river."

He looked up.

"Actually, I don't think she'll care," she said.

"Your parents came to the house again," she said, not seeing his fear. "They basically were real nice, but they told my mom they thought the car looked like a real spectacular piece of shit out here, and they told her they thought we should just get rid of it. They said they'd pay for it."

He didn't know what to say.

"Molly says your parents are gonna be here longer than they think … that getting rid of the car won't make anyone want to buy your house, no matter how you fix it."

His hands went cold.

"You know you really shouldn't be playing out here."

"This is the first time," he said.

"You're lying."

His father tended tomatoes in a small garden parallel to the house. Everywhere they lived, his parents said that year's were the best, freshest.

"Why does mom want to take the car away?"

He tamped the dirt. "Because it doesn't look good."

His father gazed at the tomato plants. "These, however, will be lovely."

"They're green, though," he said. "They don't look right."

"Just don't eat them yet." His father grinned.

He played in his own yard, gathering weeds and long grass and running it into his hair. "I'm in charge here," he said. "All of you will obey my will. That's right. Thank you for bowing." He bowed to himself and looked around. The yard was perfectly still one minute, and the next it was full of wind. Light moved in the leaves.

The grass made his hair uncomfortable, as though he'd need a shower. He brushed it off, shook it off his head, ran to the scarecar.

"Bow to me," he said. "You aren't bowing right."

When the wind quit in the trees he thought he could hear his own heart pat unevenly, but it was only a pelt of rain on the scarecar roof. By the time it was coming down hard, he was already indoors.

He and his parents stacked the cabinets full of groceries, as full as they'd been in months. Since they'd already eaten dinner, no one was hungry. They chose to sit on the porch.

The strung lights were fitted with tiny reflective screens, which caused them to sparkle a little. In a moment of silence, they could hear a low murmur from the scarecar: a pair of voices, rustling. His mother looked at his father, rose, and switched off the lights.

Black insects swarmed beneath the seat cushions, and in the sunken grooves of what used to be tires. The trunk was empty, save for leaves, but the interior of the glove compartment, which opened with a touch, glinted with the silvery wrappers of Hershey's Kisses, most of them unopened. They're hers, he decided.

He couldn't sleep that night, and when the light in his parents' room switched off, he quietly made his way downstairs and walked outside.

His feet were bare on the grass as he moved toward the car. He didn't want to go too close, in case Rachel saw him. From where he stood, he could see the lit end of a cigarette arch over the car's hood and vanish. Feeling uncomfortable and cold, he crept alongside the house to his father's tomato plants.

One of the voices was Rachel's and one was deeper. They would speak awhile and then be silent and although he was never sure what they were saying — they spoke too softly — he could understand which was which.

He plucked a green tomato from the vine and bit into it. It tasted sour, sharp.

When he realized he was crying he entered the house again, climbed the stairs and crawled in bed.

"Hey you," Rachel said, suddenly beside the car with an open beer can in her hand.

Since he'd been investigating the wreck for evidence of whatever happened the night before he blushed when he saw her. Having discovered nothing but a notebook, dampened and blank, he'd quit the search.

Rachel climbed into the front seat beside him and put her hands on the wheel.

"Where to?" she asked.

"I don't know."

She frowned, shifted the nonexistent gears into park. "We can't hang out here any longer, so I guess that's going to suck for you. Your mom and dad won, you know. They're going to take it."

"When?"

"I don't know. Maybe next week. What did you used to play here, anyway?"

"Stuff. Invasion."

"Oh, yeah? Who were you invading?"

"No one really. Just the trees."

"Well. I hope you won."

"I don't know. It doesn't matter."

"Maybe." She shrugged. "My mom said she'd pay for getting it out of here herself. I think your parents kinda shamed her into it."

"They didn't mean to," he said.

"Yeah, sure they didn't. Molly's been meaning to get rid of it for awhile. I guess she just doesn't like to think about it." She spotted the notebook in the backseat and tucked it under her arm. "She says she dreams about it, though."

"You mean driving?"

"The accident." Rachel took him in for a second, then smiled. She knew a secret. "And the car. She dreams it wakes up on her and drives under her window."

They were quiet for a minute, listening to the woods. Rachel laughed again, "She says it pulls up and it's growling under her window, but she doesn't wake up till it starts honking at her." She slapped the horn. "Honk!" She shouted, still laughing "Honk, honk!"

He shouted too, louder than she could, "Honk! Wake-up! Honk!"

"Cool down," she said. "Cool down. Just sit tight, alright? I'll tell you a story. You want to hear a story?"

"Ok."

"Ok," she said, thinking. "Well it was a real wet night, and late. Molly shouldn't have been driving that late all alone on so bad a night, but she was."

"A long time ago?" he asked.

Rachel nodded. "She was driving along like this," she said, closing her eyes and leaning back her head, "not thinking of anything, just kinda lost in the music."

"What was the music?"

"Whatever they were playing at the party. It was a big employee party, and my dad was dancing with some girl." He felt a raindrop on his hand.

"It was raining," Rachel said, turning to him, "and she was smoking a cigarette." She touched her lips and exhaled. "There were lots of different thoughts racing through her mind, like who that girl with dad was, or if she just imagined it. She was thinking about her childhood, too, even though it wasn't that long ago."

"It's pretty long now," he said.

"I guess she dropped her keys in the doorway, and it was dark and wet so she had a hard time finding them. That kinda slowed her down. She was trying to make a real big deal." Rachel growled between her teeth like a car. "She pulled out of the parking lot real angry, and everyone was running out of the party in their nice clothes and getting wet, and even the hotel manager tried to stop her, shouting, 'Come in and have some coffee!' He was pounding on the hood," she grinned, "and he cut his hand on the side of the side view mirror, real bad."

"And she had her eyes closed?"

"No, that was later," Rachel said, "first thing was she drove around for a while, trying to put herself together. The street was empty and there were lights on all the trees. She closed her eyes. She said she wanted to see what it felt like just to be floating, not to know where you were going and not to care. I guess she knew she'd crash somewhere, but she didn't know when. She said she floated like that for a long, long time, longer than she thought she could."

Her eyes stayed closed.

"She could have hit somebody," he said.

"I tell her that too. Maybe she didn't care. Anyway she didn't remember anything until after the crash, when she couldn't feel half her face, and her back hurt bad. She's had like five operations on it now."

The rain was coming down.

"How old were you then?" he asked.

"I was barely there," She said.

The morning they pulled the car out of Molly's yard was several weeks into the school year. He caught a glimpse of Molly from his window, puttering around in her garden. It was noon and the sun was bright, so he couldn't see the side of her face with the eye patch, couldn't see the real thing like he wanted to.

Original art courtesy Rob Grom.