LOST PLACE  |

FEBRUARY 2006 – NO. 3 |

|

|

History's Mornings

Each July, I celebrate the day of Custer's Massacre at the Little Big Horn. I celebrate it for the howling joy I feel in his defeat, the last high-water-mark for Native Americans in their fight against whites' move west. Custer, earlier, had led his troops in what laughably came to be called the Battle of the Washita, when he attacked a sleeping village at dawn in the snow. General George Crook did the same thing in the run-up to the Custer fight. It takes a real man to shoot a woman or a child in the pre-dawn cold.

My feelings about Native American history come naturally, for when I was a boy, my father took my brother and me into what was at that time the great Keowee Valley in northwestern South Carolina, and that land was the trail way of empires. We tramped the land and swam in the river, which poured straight from the mountains, cold and clear over watersmooth stones.

The land there was as glorious as it was on February 16, 1760 — a river as picturesque as any in America, bubbling through the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains. The bottomland was incredibly fertile, and for more than 2000 years at least, Indians had lived there, growing crops, killing meat, taking fish. My first visit to the valley was lost in the veil of my early childhood, but we went frequently because of my father's obsession with Indians and with his and my mother's own homeland.

The Oconee County side of the Keowee River was the site of a large Cherokee Indian village called Keowee, one of several of the so-called Lower Towns, a once-flourishing empire of accomplished and intelligent people whose land stretched northwestward more than a hundred miles into the high mountains.

Those were parlous times, with alliances shifting constantly between Indian tribes, between the French and the British, between South Carolinians and Virginians. Fearful of attacks, the Lower Cherokees asked for a fort, which the British were only too happy to build. In those days, this was the true frontier, as alien to soldiers and settlers as the West was to Lewis and Clark nearly half a century later, and in 1753, the British built Fort Prince George across the river on what is now the Pickens County side. It was a standard British military outpost — a small square fort with elongated, diamond-shaped bastions. The fort was about 200 feet from "salient angle to salient angle," and was crammed full of buildings, with a well in the center.

There were long stretches of peace, but by the time of the French and Indian War the area was a battlefield, and though there were a few traders and soldiers who knew and understood the lifeways of the Cherokees, most couldn't understand why they didn't act like proper British citizens.

Like all good stories, there was a villain in this one, and his name was Lt. Richard Coytmore, a vain and stupid commander who had taken over Ft. Prince George during the war. Worse than his vanity (which was huge) was his arrogance and his belief that the Indians, to use the common parlance of the 18th and 19th centuries, were savages. So when I think of the attacks at dawn in the Western Indian wars — egregious events perpetrated by Custer and Crook — I see a delicious irony of the events of February 16, 1760.

Times were terrible for everyone in this region in the mid-1700s. The fort was full of disease, and the village of Keowee was in a bad way. Fighting had been going on for months, and the Cherokees, naked and freezing, did not know whom to trust. They knew well enough, however, that Coytmore's presence was disastrous. Not long before, they had spotted him during a traditional dance in Keowee, drunk and making fun of the Indians. And his manner, even according to reports of his own men, was brusque and even cruel.

On this morning, the great Cherokee chief Oconostota sent word that he wanted to see Coytmore at the ford in the river. Disgusted at having to be awakened on a cold, snowy morning, one in which fog lay heavy on the water, Coytmore roused himself and walked the few hundred yards from the fort to the river with an Ensign Bell; a trader, Cornelius Dougherty; and a translator named Foster.

Oconostota was on the Keowee side of the river, and he shouted something out in Cherokee, which Foster translated as "I want a white man to go with me to Town," meaning Charles Town, which was several hundred miles to the south. Relieved, Coytmore told Forster, "Tell him if that's all he wants I will get somebody to go with him."

"Then I will catch a horse!" cried Oconostota. At that point, the Indian chief whirled a bridle around his head, and shots rang out from the underbrush along the river. Bell took a bullet in the calf, and Forster got it in the ass, which leaves no doubt about which way he was headed. Coytmore took a ball through a lung, which, from 50 or 60 yards away, has to be counted a pretty good shot with a smooth-bore musket.

The others dragged Coytmore back to the fort, where he managed to live for a while before expiring. After his death, there was a massacre of Indian hostages in the fort that is one of the great unknown events in American history. Unarmed men were hacked to bits.

That morning changed the history of the frontier. Whatever justice the Cherokees saw in killing Coytmore, his death, like the Battle of the Little Bighorn, was ultimately a pyrrhic victory.

*

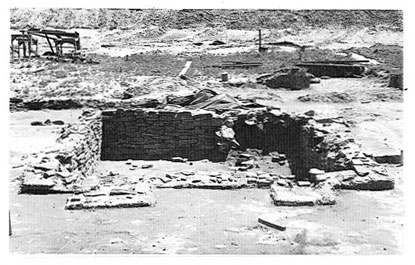

Flash forward to another morning, 208 years later in 1968. For weeks, crews have been cutting down all the trees in the glorious Keowee Valley because the Duke Power Company is about to impound a lake that will flood the entire area with water a hundred feet deep. Two archaeologists, John Combes and Don Robertson, are leading the dig.

I am 18 years old, and my brother Mark, our father, and I have been working off and on for months as volunteers with an archaeologist from the University of South Carolina who is racing the calendar to excavate Fort Prince George, which has for decades been buried in the earth and more or less forgotten, though local people know where it was supposed to have existed. The valley it's in, one of the most beautiful in the southern United States, has been destroyed and will soon be covered with 18,500 acres of water and 300 miles of shoreline. I feel literally sick every time I see it, and I know Mark and our father do, too. I have come to think of the 1960s as America's Last Period of Gullibility, when it could be over-awed by utility companies to such an extent they would allow their heritage to be raped. People know about this mostly from the West, but it happened all over the South, too.

We have no time for polemics, though. It's early on a foggy spring morning, and we have already uncovered the clear outlines of the fort, bastions and all. We have found the skeleton of a man whom we all believe is Lt. Coytmore. We know his body was buried inside the fort, and it's the only such burial here. Looking on his skeleton, laid out neatly, I feel a shudder of sorrow for the man and his stupidities. What is man, that Thou are mindful of him? Lt. Richard Coytmore may have been many things, but I have serious doubts that he was but "a little lower than the angels."

Our job this early spring morning, however, involves a stone building, whose gray mass we discovered fairly early in the excavations. Probably by the late 1770s, the building had collapsed, and someone, maybe a farmer, had pushed all the stones into the building's cellar and covered it over with topsoil for farming. Generations planted crops right on top of Coytmore and this structure without really knowing it. (Local legend had never lost the location of the fort, however, even though no one had really studied it in the two centuries since it came down.)

The fog lies heavily on the river this morning, an omen for those so inclined. We have decided to empty the building's foundation of its stones, most the size of a medicine ball and weighing perhaps 30 or 40 pounds each. We have to take the rocks, once a wall in a British colonial fort, about a hundred yards away, past the outlines of the fort to a spot near the existing road. We do not know what we will find at the bottom of the rocks, but the feeling of the crew is not, I imagine, unlike that of Lord Carnarvon and Howard Carter in Egypt's Valley of the Kings in the fall of 1922.

I have learned, on this dig, to use a whisk broom or a paintbrush to clean around the most delicate of artifacts — the base of a rum jug, an iron drainage grate, the stem of a wineglass. Today's job is grunt work, however, and we take turns with the jobs. Wearing heavy work gloves, we remove the rocks from the cellar and place them in heavy, construction wheelbarrows. For a long time, I pick up rocks and toss them into the wide-mawed barrows, where they hit with a muffled thud. I look toward the river, a lovely place I have known intimately for more than a decade, and see the trees gone, the landscape as blasted and barren as Mars. Over the years, I will have ample opportunity to forgive and forget, to see the deep blue waters of Lake Keowee and know the pleasure they bring thousands. I will never forget, though, and I cannot forgive. If one can commit genocide upon the land, this is it.

My turn has come for wheelbarrow duty. We switch places, and I begin trundling the back-straining loads of stone through the fort, past the outer walls, over what was once a moat, and to the edge of the road. Sadly, no official report will ever be written on Fort Prince George, though 30 years later, my father will pen a monograph that's part history and part memoir that the University of South Carolina will publish.

The work is dull and long. Despite the fact that the morning is very cool, I am soon sweating through my clothes but enjoying the pull of stone against muscle. It is not yet mid-morning, and the sun begins to tear the clouds apart, like ripping wool. The fog isn't quite ready to dissolve, though, clinging to the river bottom as it has for millennia. I almost wish the mist were sentient, able to understand that its own days covering this ground are numbered.

I drone on, and on perhaps my fifteenth wheelbarrow load of rocks from the cellar, I turn it up with a groan, and just then, the sun spikes through the clouds and fog and cuts along a rock I have just turned over. The rock has landed just-so, and on its surface there appear to be markings of some kind. I inhale sharply. The sun's rays spear violently into the stone, and I see numbers deeply etched on it.

I reach for the rock with my gloved hand and brush it off, and it appears to be the numbers "194," and my mind fails to connect this to anything. My first thought: This must be some kind of geodesic marker placed here during the WWII years. But then I realize that's impossible. Nineteen Forty-What? I brush harder and then, with my breath growing ragged, I lift the rock and gently turn it over. It's not very large, perhaps 12 or 15 pounds. The sunlight knocks a river of knowledge into me. It is a full and clear date that has been carved into the rock: 1761. I begin walking back toward the other, straight into the sunlight, and I can't get my breath.

Oh my God, I think: It's the cornerstone of the stone building, which might have been a powder magazine. Now, halfway to the fort's heart, I see another date in smaller, less-certain carving just below it: 1770, and I register another event that happened that year, one I would know well enough in my classical-music-rich household: the year of Beethoven's birth, half a world away.

By the time I get back, my hands are shaking, the morning had ripped back the shroud of fog in the Keowee Valley, and I say the only thing that I can blurt out: "I've found something. You better come look at this." I still can't quite believe it. The others climb out of the cellar and come slowly to me, not expecting much but grateful for a small break in the aching labor.

"I don't believe it!" my father cries when he sees it. Mark is jubilant. The others whack me on the back, crow and shout. I don't know how Howard Carter felt exactly when he first peered into Tutankhamen's tomb, but I have a good idea, one that will stay with me all my life. The strange fortune of archaeology has uncovered an artifact that by all rules should never have been discovered.

Two things conspired: Sheer luck and the sun tearing the mist into meteorological wreckage. We take a coffee break and admire the cornerstone and talk excitedly about the discovery, about history, about salvage archaeology. For years after that, we will relive the moment, and I will hone the story in my telling, the way Cherokees refined their stories for hundreds of years.

The rock, the proof that this was indeed long-buried Fort Prince George was, of course, taken to the archaeological collections at the University of South Carolina, and I have never seen it again, though I have a spectacular photograph of it taken that morning by my father. The morning light is full and strong upon the year 1761.

*

Another morning, more than 30 years later. Mark and I have passed 50, and with our father, still vigorous as he nears 80, we are driving to the Keowee-Toxaway Visitor's Center, which lies at the upper end of what is now Lake Keowee. We are going to see our father's scale model of Ft. Prince George, which he built more than two decades before and placed on semi-permanent loan to the center, which was built to focus on the area's natural and human history. The model fort's sides are about two feet long.

The entire glorious Keowee Valley went under water in May 1968, and our father was one of the few people — if not the only one — to see its demise. He drove to a spot in the hills high above the valley and watched as the waters spilled from the Keowee River and flowed over the site of the fort, the village of Keowee, and the ford where Lt. Coytmore had been shot. A veteran of the Army Air Corps in WWII, he stood ramrod straight and gave his best military salute as the valley died.

In my calmer hours, I can admit that the lake is gorgeous, that it supplies power, and that nature itself changes the natural world as much as man has. These are feelings that are forced from my soul by a desire for fairness, however, and the truth is indelible. The value of what went under the waters of this new lake was incalculable.

This morning summer has settled its strong humid warmth over the South, but even when we park and get out, the air here, in the far northwestern corner of South Carolina, is almost sweet enough to sip through a straw. The Visitor's Center needs some work, but it's reasonably well maintained. A succession of small buildings tumbles through the woods with clots of rhododendron and mountain laurel as neighbors. In each building there is a display of history, along with artifacts, artwork, and verbal descriptions of the area's history.

We come to the building housing my father's fort, and there it is. He took incredible care building it to absolute scale, making well-educated guesses when we weren't sure of some facts. (The outlines of the buildings were clear enough during our excavations, and we easily found the well in the center of the fort. We dug it down as far as we dared, and Mark, always more courageous than I, allowed himself to be lowered far down into the hole to look for artifacts. Alas, the water table on the river was obviously high, and we never found the well's bottom.)

There's no sentimentality in this place. We cast a careful eye on my father's fort's condition, and it's certainly far better than what the real fort endured during its twenty-odd years of service to the Crown and then as a trading post. But there are the few odd roach husks near the model, and that irritates our father, who put untold hours of work into the model. To my mind, this is a serious contribution to the history of the area, now to the maintenance of the region's memory, but no casual observer of the display would have a clue of our years in the Keowee Valley and how our knowledge of the fort changed that foggy morning I found a single stone.

Although, as my father notes, "the appearance of the fort was constantly changing during the 15 years of its existence," the model presents the probable appearance of the fort in the autumn of 1761. The scale of the model is 0.9 inch equals five feet, and my father spent more than three years on its research and construction.

I walk past my brother and father as we head back toward the car, hiking slowly up the sharp slopes in the luxurious shade. The morning is thick with the hidden nets of spiders, and I walk face-first into them and turn into a swatting thing. Few others are about, even though it's a sunny Saturday. Most people would be out there on the lake with their expensive boats, their noises sounding far above where Fort Prince George rests under a fog comprised largely now of diesel.

Without my father's model, the fort would be more rumor than fact to most people. In a small way, we took what had been lost for two centuries and brought it back into history, restored its shapes and its sense to a newer world.

One artifact — a modern-one — does mark the site of Fort Prince George. My father built a time capsule just before the water rose over the site, a box made of one-eighth-inch-thick brass plate soldered together. In the box, he put two thick lead plates, two stainless steel plates, a plastic envelope, and two coins. Stamped with a die tool into the lead and steel plates was this message:

"This marks the site of Fort Prince George, built by the British in 1753. Excavated in 1968 by John Combes, Don Robertson, and Marshall Williams." The coins were a 1968 nickel and a 1968 penny. My father buried the box 18 inches deep in the center of the southeast bastion, on the south side of a large rock.

The power company closed the dam, and the waters spilled over Fort Prince George and Keowee on May 12, 1968. It was Mother's Day.

This essay, "History's Mornings," is from the author's forthcoming book In the Morning: Reflections Toward First Light, which will be published by Mercer University Press in the fall of 2006.