LOST THING  |

MAY 2008 – NO. 24 |

|

|

Lost Balls

Golf is a curious vice. Satisfaction isn't guaranteed — it's fleeting at best — but the addiction is insidious and sure. What can we expect from a sport where the absolute best in the world regularly screw up?

My perspective on the game is not the one seen in books and calendars of players with perfect swings on impossibly great courses in exotic locales. Not the straight-down-the-middle approach. Gigantic hooks and pushes take me into ankle-deep muck, far from the fairway, fighting the sagebrush, dodging the poison ivy, and looking for a white orb as round as the moon and equally uninterested in my predicament.

The six handicap of my youth has grown huge through decades of neglect. The concept for Lost Balls evolved from the depths of this realization, not so much a sharing of misery as a celebration of it.

The golf shot, with its aspiration, trajectory, and distance, seems to mirror human ambition, to take measure of our successes and failures. Of course those who don't play see only the surface details: ricocheting balls, mammoth mowers, cowering onlookers, and loud, angry men wearing funny clothes, their clubs flailing, speaking a language all their own. But there is so much more to the game, its history, culture, and interaction with nature. I decided that a different story could be told.

Obviously I'm not the only hacker around. So I started looking out-of-bounds, outside the box, for what certain pleasure must be there. In swamps, dunes, deserts, and woods across America, I found hundreds of golf balls, a full century of future stratigraphy, the detritus of wishful players' misplaced hopes and of an enormously fertile industry. I smiled as the wildlife cautiously observed me as I photographed, an ambassador from the upright species that pelts their territory. And as I looked over my shoulder on the way back to the green, I often wondered if nature was in fact mocking me.

Everywhere there are lost golf balls — stuck up in trees, lodged in birds' nests, embedded in cacti, gathering on coral reefs, and layering the wetlands like Hansel and Gretel cookie-crumb messages left to be deciphered. In the course of my hunting, I discovered a curious language on the balls themselves, a veritable Rosetta Stone of knowledge: Pluto, Bambi, Long and Straight, Wanker, and Revelation. I met collectors of rare and antique golf balls — who knew they existed? — and even had a chance to photograph what is believed to be the oldest golf ball in the world.

I traveled to Ireland and then on to Scotland, where pagan shepherds once whacked rocks into rabbit holes and where my forebears came from. There the game is played quickly, in wind and weather, closer to nature, closer to sheep.

But even if golf's roots are in the heather and earth, hazards with names such as Hell's Half Acre, the Devil's Asshole, and the Church Pews often make it seem more like navigating a Protestant-inspired minefield laced with opportunities for sin and redemption in the Garden of Eden.

I dutifully read a stack of books with titles such as Zen Golf This and Tiger Says That, searching for knowledge and a cure for my ailing game. My wife smirked as the pile of books grew. But there were no miracles — rather an ongoing tug-of-war between strokes of genius and far more frequent disappointments.

The game of golf challenged my healthy sense of self-esteem. In photography you edit out the bad shots; in golf you're condemned to live with them. Still, I wondered, how difficult can it possibly be? Murphy's Law and quantum physics agree that almost nothing in life behaves as you'd like it to — not children, politicians, or pets, and least of all a small white ball destined for a distant hole in the ground.

So perhaps the true gift that golf offers us is the time spent with friends and in nature — the more nature the better — in a state of perpetual folly, witnessing one another's strengths and shortcomings and humans' tendency to behave like beasts.

It seems likely that leisure sports evolved from Neanderthal combat and hunting. In golf there is no life or death; the dangers are mainly errant balls and battered egos. Yet, like a spear placed perfectly behind a mammoth's shoulder blade, a great golf shot is something to behold, something to seek, seemingly at any cost. Which is why we keep swinging, groaning, practicing, and shaking our fists at the all-too-rare miracle of the perfect shot.

There is a golf ball on the moon, left behind by Alan Shepard, but I hear the course isn't very well maintained.

Concentrate, align, exhale, focus, slowly now, whoosh … fore!

Professional Golf Ball hunter at Tuxedo Club, New York.

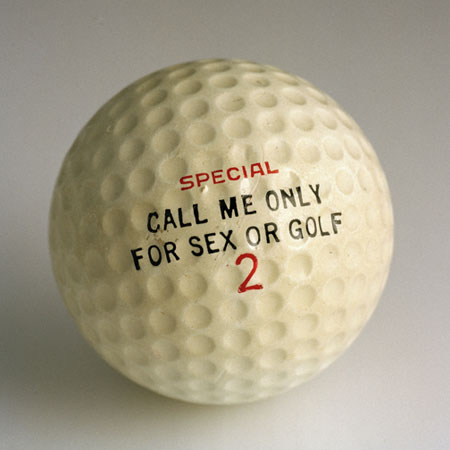

Sex Golf Ball, 1950s.

Broken feathery Golf Ball, Scotland, 1840?

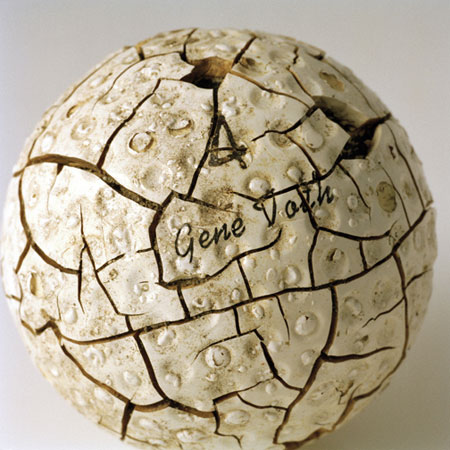

Cracked Gene Voth ball from the 1940s, given to me by the ball hunter at Tuxedo.

Golf Ball in a bell jar from an incident in Scotland in the 1890s when this ball struck a woman in the head, knocked her unconscious, and remained impaled on her hair pin. North Berwick, Scotland.

Lost golf balls on the creek bed at Blue Lakes Country Club, Twin Falls, Idaho.

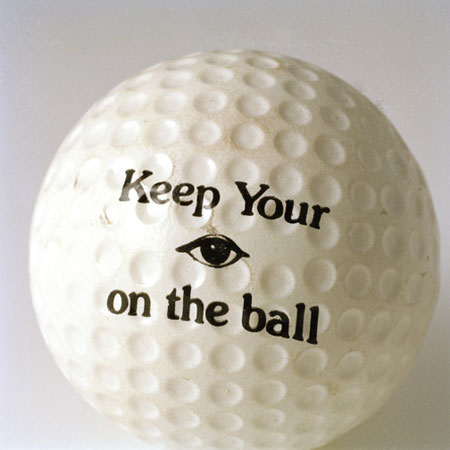

1960s Keep Your Eye on the Ball.

Excerpted from Lost Balls: Great Holes, Tough Shots, and Bad Lies by Charles Lindsay, by permission of the author and courtesy Little, Brown and Company. Copyright © 2005 by Charles Lindsay. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Photos courtesy Charles Lindsay.