FICTION  |

NOVEMBER 2006 – NO. 10 |

|

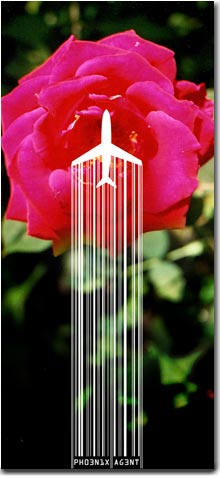

The Phoenix Agent

He was tall and good-looking and fiftyish — older than her mother, but not what you would call old. He was deeply tanned, with character lines at the corners of his eyes that suggested he either did a lot of squinting into the sun, or laughed a lot, or maybe both. He looked to her like one of those White Hunters you saw in the black-and-white jungle films that turned up on the movie channels — one of those men who was always seducing the wife of the rich guy who was paying for the safari but was wimpy to the core. This man was too cool.

Cinda had never seen him before. She'd been working at the EcoMart since the start of her senior year — now graduation was only a week away — and she was almost sure this was his first appearance in the store. And if she'd needed confirmation, she got it almost immediately while she was ringing him up.

"This is quite a market," he said. "A terrific selection of health stuff."

"We think so," she said. She was in the midst of scanning his "stuff" — nut bread, organic peanut butter, broccoli and carrots. "We're not as big as the chains, like Whole Foods, but people like us."

"The personality makes a difference." He was leaning in to read her name tag. "Folks like you, Cinda."

"Thank you." Now she was wary. Was he hitting on her, like some kind of pervo creep, or was he really being nice? She went on scanning his purchases: milk, deli turkey slices, two boxes of loose tea. The jumbo box of detergent he had let stay in the cart, and she reached over the counter to hit the product code with the hand scanner.

"Good shot," the man said.

"Excuse me?" She rang up his total.

"It always impresses me, the way checkout clerks zap the UPC's — like a cowboy shooting from the saddle."

"Your total is $18.80," Cinda said. She began putting the groceries into paper bags.

He held a credit card out to her. "What do you suppose is the range of one of those things?"

She took the card and slid it through the reader. "Range?" she said.

"How far away can you stand and still hit the code?"

She looked at the front of the card — Brian Hansen — and the signature on the back, before she handed it back to him. "I've no idea," she said.

*

Cinda told her mother about Brian Hansen over supper that evening.

"He's sort of a hunk," she said, "but weird, you know?"

"It sounds as if he was just being friendly," her mother said. "Making conversation."

"Some conversation: how good a shot am I with the stupid scanner."

"You say you've never seen him before," her mother went on. "If he's new in Orlando he probably doesn't have many friends. You can't blame him for reaching out."

Cinda looked scornful. "Is that what you call it? 'Reaching out'?"

"Don't poke fun," her mother said.

"And anyway, how do you know he's not just a handsome pedophile? And what he's actually reaching out for, you wouldn't care to know."

"Cinda," her mother said.

Mother disapproved of worst-case scenarios.

*

"It's a curious name: Cinda," Brian Hansen said. "I mean it's unusual."

This was the second time she'd checked him out. Whether it was only the second time he'd shopped at EcoMart, she couldn't say, since she worked only Sundays and Wednesdays.

"It's just Linda with a 'C'," she said. "Your total is $12.26."

This time he gave her a twenty, one of the newer bills with the giant numbers so nursing-home types could read them. You had to hold up the twenties and look for the little silver thread; if somebody gave you a fifty or a hundred, you had to call for the supervisor.

"I'm sure it's real," Hansen said. "I just got it from your ATM at the back of the store."

"You never know who to trust," Cinda said. "Your change is $7.74." She put the coins in his palm and laid the bills on top of them.

"That's very good," he said.

"Excuse me?"

"Some clerks put the coins on top of the bills — so they can slide off."

"I don't even think about it," she said. "Have a nice day."

He picked up the brown bag. "Have you tested the range of that hand scanner?" He made a pistol of his free hand — forefinger aimed and thumb cocked. "Zap," he said. "I wonder if it could read the code on that TV Guide at the next checkout stand."

"I seriously doubt it," she said. The magazine was on a rack that was about five feet away, and the product code was half covered by an astrology paperback.

"Have you tried it?"

"I have better things to do."

She began sliding the next customer's items across the scanner glass. Brian Hansen cradled his bag of groceries and moved away.

"You should give it a shot," he said. "A fair test."

*

"What does this Hansen person look like?" her mother wanted to know. "You're certainly paying a lot of attention to him."

"Because he pays attention to me," Cinda said. They were sitting by the pool, side by side on plastic deck chairs. It was Saturday afternoon, early May, hot. "I don't invite it. Honestly."

"Does he remind you of your father?"

"God, Mother. No, he does not remind me of Daddy. Besides, I don't remember Daddy all that well." She squeezed sunblock into her hand and smeared the goop on her legs. "He looks kind of like an over-the-hill lifeguard. Tanned, bushy hair that's going gray around his ears, blue eyes — that really pale blue, you know? So pale, he might have come from The Village of the Damned."

"Is that a book?"

"A horror movie. All the children in the village have eyes with pupils so pale and washed out, you can, like, see right into their heads."

Mother wrinkled her nose. "Not my idea of handsome," she said.

"No, but he is. A nice shy smile. A husky voice, like maybe he's a smoker — except he isn't, because I can smell nicotine a mile off."

Her mother smiled and gave a mock sigh. "A shame he's too old for you."

"But not for you," Cinda said. "For you he'd be just right."

"Said the baby bear."

"It's his fussiness that's the only drawback." Cinda stretched and stood up. She pulled the bottom edges of the swimsuit over her buttocks and went into the water. She stood on the floor of the pool, her elbows on the edge, her chin in her hands. "Who notices whether you put the change on top of the dollar bills, or the dollar bills on top of the change? Who the hell cares?"

"Language, Cinda," her mother said.

*

Just at the end of her shift the next day, she saw Brian Hansen go through Veronica Ivey's checkout lane, and she wondered what he was saying to Ronnie — did he have a regular "line" that he practiced on every cashier he met, or what. She ran the total on her register tape and carried the money drawer into the cash-up room behind the deli section.

She finished counting down her day's receipts, then went to the back room to clock out. When she was done with that, and tossed her apron into the laundry hamper, she gathered up her bag and went to wait for Mother. Hansen was sitting at one of the tables at the front of the store, eating a deli sandwich and drinking an organic soda. His bag of groceries sat at his elbow.

"Hello," he said. "The line was shorter at Veronica's register, so I stood you up."

"No problem," Cinda said. "We both work for the same company."

"She puts the coins on top," he said.

"Oh, my God," Cinda said. She hitched the bag higher on her shoulder. "Please don't get her fired."

He smiled. "I bet you're waiting for your mom," he said. "Can I buy you a drink?"

"No, thanks." She sat across the table from him. "But thank you for offering."

"That door behind the deli department," Hansen said. "Is that where the cashiers add up the day's receipts?"

"Yes."

"If the money in your cash drawer doesn't match the total on the register tape, do you girls have to make up the difference?"

"We have to count down until it balances. And it isn't only cash. There's credit card slips, and usually a few checks, and store coupons — a lot of different sub-counts." She frowned at him. "Why? Are you planning to rob the store?"

He looked surprised. "What makes you say that?"

"Your curiosity about how we do things. How we count the receipts. All your questions."

"Would I get away with it?"

She shrugged. "Probably not. Especially if you tried to hold us up with a scanner gun."

He laughed — a kind of bark, short and finished, as if he didn't want to make too much out of laughing. "Right," he said. "Then it's a good thing I'm not a holdup man."

She dragged her bag up to the top of the table, to get the weight of it off her shoulder.

"What is your work?" she said. "If robbery's not it."

"I'm almost sorry you asked," he said. "It so happens that I'm between jobs right now, taking a sort of vacation."

"Did you get fired?"

He smiled. "No. I quit."

"That's what everybody says."

"Though in this case it's true," he said. "I had a disagreement with the boss, and I left the company. It was basically a breach of trust."

Cinda looked past him, out the windows to the parking lot. Her mother had left the Volvo wagon in the EcoMart fire lane and was coming into the store.

"Here's my mother," Cinda said. "Illegally parked as usual."

Hansen turned to look as her mother came toward them.

"Mother, this is Mr. Hansen," Cinda said. "The man I've been telling you about."

Hansen stood and bobbed his head. "Brian," he said.

Her mother extended her hand to let Hansen touch it, then withdrew it. "Beth," she said. "My daughter tells me you're a great person for details."

He looked amused. "Did she?" he said. "Then it must be true." He slid back into his seat. "Your daughter has what we call 'a keen eye'."

"Do you have children, Mr. Hansen?"

"A daughter, as it happens."

"Then you know about the judgments of the young." She nudged Cinda's shoulder. "Come on, babe. We have to go."

Everyone stood.

"I'll walk out with you," Hansen said, and he waited while Fat Alan Dolby, the assistant supervisor, pawed through Cinda's bag for stolen items.

"Talk about breach of trust," Cinda said.

"That's my blue Chevy just across the way." Hansen pointed. The rear license plate read: Arizona and, in smaller letters, Grand Canyon State, under a picture of the kind of cactus you saw in Road Runner cartoons.

"I thought the Grand Canyon was in Colorado," Cinda said.

"You see," said her mother, "you don't know everything."

"Nobody does," Hansen said. "It was a pleasure meeting you, Beth." He gave them a small wave and went to the blue car, his bag of groceries nested in one arm.

When they were in the Volvo, Cinda said, "Didn't you like him?"

"He seemed quite personable."

"I think we should invite him to dinner."

Her mother started the engine. "Let's not rush things," she said.

*

A week later, Brian Hansen was sitting with them at the dining-room table, drinking a white wine spritzer and talking with Mother as if the two of them were old school chums.

"Is it really Beth?" he was saying. "Or is Beth short for Elizabeth?"

"I don't confess this to everybody," Mother said, "but it's short for Bethany."

He looked surprised.

"You mustn't tease me," Cinda's mother said. "Please."

"I wouldn't think of it. Bethany is unique."

"So is Cinda," Cinda said. "By the way."

Not that she felt left out or anything.

"Cinda says you're new in Orlando," her mother said. "Where have you come from?"

"I lived in Phoenix until a few months ago," he said. "Well — Scottsdale, to be precise, but same difference."

"And what brought you here?"

"Mother," Cinda said. "It's rude to pry."

"We're only talking," her mother said. "Nobody's prying."

"And I don't mind the question," Hansen said. "The truth is, I'm not sure why I picked this part of the world. Except there looked to be a lot of possibilities. All the activity at Canaveral — the shuttle launches, the cruises — and what you people down here call "the attractions" — Disney and Universal and Sea World. You know." He stopped and looked at his hands, which had short fingernails clipped almost straight across, not curved to follow their natural shape. "And a little bit of nostalgia, too."

"So you'd been here before," Mother said.

"I'd brought Ruby here — my daughter — when she was 13. We went to Disney."

Ruby. How lame was that? And he was the one who'd made a thing out of Cinda.

"When was that?" Cinda asked.

"Years ago. Twenty plus. The town was a lot different then."

Twenty-plus years ago, she wasn't even on the horizon and her parents were still married.

"Where is Ruby now?" her mother wanted to know.

"I didn't mean to mislead you," he said. "She's dead."

There was an excruciating silence. Finally, Cinda's mother said she was sorry to hear that; it almost sounded as if she'd had something to do with Ruby dying.

"She was on that flight that blew up over Scotland."

"Lockerbie," Mother said. "I remember. All those people."

Jesus, Cinda thought. The poor man.

"Two-hundred fifty-nine on the plane," Hansen said. "Eleven on the ground."

Details again.

"It must have been dreadful for you," Mother said.

"Excuse me," Cinda said, rising, "but I've got a last-minute term paper to take care of." If this was the gloomy direction the talk was going in, she'd prefer watching television in her room.

*

The next time Hansen came into the EcoMart on her shift, Cinda was on break. Outside the store, on the cement apron between the entrance and the parking lot, were patio tables and metal chairs with mesh seats, and she was sitting alone with a can of Diet Coke she had brought from home. She saw his car as it entered the lot, watched him park between a pair of SUVs that made his Chevy disappear. When he emerged he smiled and headed straight for her.

"Are you malingering?" he said.

She scowled at him. "What's that supposed to mean?"

"Loafing," he said. "Goofing off."

"I'm on break," Cinda said. "It's part of the contract we have with EcoMart. I'm not bending any rules."

"I meant to be joking," Hansen said. "I must be losing my touch."

Cinda took a last swallow from the Coke can and set it aside.

"I think I've got you figured out," she said. "You do some kind of security job. Used to. That's why you ask so many questions."

Hansen looked embarrassed. "Something like that," he said.

"I tried my theory out on Mother. She agreed with me, and she said she hopes you find a situation that suits you."

"Thank you both."

"And we were both of us really sorry about your daughter," Cinda said. "I didn't mean to be rude when I walked out the other day. I just couldn't deal with it at the time."

"I wasn't offended," Hansen said. "I shouldn't even have mentioned Lockerbie. It's my problem, and it was a really long time ago."

"Mother says it was a terrorist bomb."

Hansen looked grim. "That was in the days when they were careless about screening baggage," he said. "Nowadays it's better — a little."

"Mother's taking me to London for Christmas," Cinda said. "It's my reward for escaping high school."

"I haven't been to Britain since '88," Hansen said. "I had to go over to claim the body. What was left of it."

Was he trying to make her uncomfortable all over again? She hoped he was just talking, just being himself, but how were you supposed to react to somebody else's grief? She really couldn't cope with it.

"You'll have to excuse me," she said. She gathered in her Coke can and stood up. "They only give us ten minutes."

"That's fine," Hansen said. He was smiling again, so it was all right. "I was on my way to the bank. I only stopped off to say hello when I saw you malingering."

"Whatever you want to think," Cinda said. Then she said, "Are you some kind of secret agent?"

Now he laughed. "You know what, Cinda? You pretend to be tough, but you're really a romantic."

*

Off and on through the summer, Brian Hansen was their guest. Sometimes he came for lunch, once in a while dinner; rarely, on Saturday afternoons, he would sit by the pool with Cinda and her mother. Mother would make martinis and serve them in pastel-colored plastic glasses with clear stems. Cinda would drink diet ginger ale and try to get a word in edgewise.

"I don't know if you've noticed," Cinda would say, "but a lot of the people who shop in a health food store don't look particularly healthy. I used to think the customers at EcoMart shopped with us because they wanted to improve their health. Now I think maybe eating health food is bad for them, and that's why they look the way they do."

"Chicken and egg," Hansen said. "Which comes first, the health food or the poor health?"

"Exactly."

"I like your mind," he said. "Some investigators would call you cynical. But others would say you're original."

"And what do you think, Brian?" Cinda's mother wanted to know.

Hansen smiled. "Original, of course. Like her mother."

Which was the lamest, fakest kind of flattery, but Mother ate it up. She looked forward to Hansen's visits, and usually managed to have a hair appointment the day before he was to stop by.

"I think you're interested in him," Cinda said later.

"He's pleasant company," her mother said. "Not like several men I won't name."

Cinda could name them all, but didn't.

*

At one of their poolside Saturdays, it came out that in September Cinda would be studying art and design in Savannah.

"I'm not surprised to find out you're artistic," Hansen said. "It shows up in the way you do your work at the store — your concentration, your poise."

What was all that? His ice-blue eyes were melting all over her, and for an instant her early picture of Brian Hansen as deviant flickered in her mind's eye. Or perhaps he meant to look fatherly, which she thought was slightly worse than being a pervert.

Mother saved the moment. "That remains to be seen," she said. "Especially the 'concentration' part."

"Not to mention the 'poise' part," Cinda added.

"But you must be excited about it," Hansen said.

"Mostly I don't give it much thought. Every now and then I'll stop in the middle of doing something and I'll get this weird, like, swoosh in the pit of my stomach — and then I think how different my life is going to be, and how I won't be around the people I've got used to being around." She ducked her head in the direction of her mother. "But I haven't freaked out. Not yet anyway."

"What made you pick Savannah?"

"Cinda's always been a doodler," her mother said. As if that answered the question.

"My art teacher gave me a whole bunch of brochures," Cinda said. "I wrote to half-a-dozen places."

"She really wanted to go to Chicago--to the Art Institute."

"No, I didn't," Cinda said. "That's where you wanted me to go."

Mother gave Hansen her famous helpless look. "I only wanted the best for Cinda."

"Whether Cinda wants it or not."

Hansen laughed and clapped his hands, as if he'd just heard a joke. "You wait, young lady" he began, and Cinda interrupted him.

"If you're going to tell me to wait till I'm a mother myself," she said, "please just don't."

*

The worst time was the day Hansen and Mother got into a semi-argument about terrorism, and bombs, and airplanes.

"I can't even hear a plane flying over the house," her mother said, "without thinking of 9/11."

Which was a bizarre thing for her to say, because when the wind was from the south, as it often was, the flight path to OIA was right over their pool. If Mother reacted to every plane she heard, she'd never think of anything except 9/11.

But Hansen went right along with it. "I know," he said. "I was the same way. Bad images linger."

"I can't tell you how it upsets me," Mother said. "I'll be watching a Friends rerun — and all at once there are the twin towers, half their windows lighted up, and I think, 'Oh, dear God'."

"It's distressing," he said.

"I wish they could go back through all the old TV shows and movies and magazine ads, and somehow remove them — the towers — just edit them out. Make them disappear as if they'd never existed and three thousand people hadn't died in them when they fell."

"But it wouldn't bring any of them back to life."

"I never said it would." Her mother sounded peevish.

"And you know what else?" Hansen said. "Now we can appreciate the others. The Chrysler Building. The Woolworth Building. The Empire State. Those are the real skyscrapers. Those show imagination, and spirit, and beauty, and splendor."

Splendor. That was a word you didn't hear much.

"Three thousand human beings, dead," her mother said, as if that was her only point after all. "How can you forget?"

He looked down at his empty martini glass. "I can't," he said. "But I think when you screw something up, you have to put the best possible face on it."

Cinda sat at the side of the pool and listened. Whenever she looked up at an airplane, she didn't see a second plane exploding into the Trade Center and she didn't think about three thousand people dead. She didn't see a plane filled with college students, thinking they were going to be home for the holidays, not dreaming the world was about to end. She only imagined a couple of hundred seats in coach filled with a bunch of parents — more moms than dads--and bratty kids on their way to Disney World.

"It's all what your generation calls a 'flashback'," Cinda said. "If you asked me, I'd tell you both to stop watching those re-runs on television."

It seemed a simple enough piece of advice, but that night after she went to bed Cinda lay awake considering the difference between her mother and Brian Hansen. Her mother was upset by a tragedy that truly didn't concern her. She didn't know anybody who had died in the collapse of the Trade Center towers; she didn't even have friends who knew anybody who died there. She was reacting — even though she might be reacting genuinely — to pictures on a television screen.

Cinda had seen the same pictures, though not live — she was in English class when it happened — and she had seen commercial flights overhead, sitcom repeats showing landmarks that no longer existed, out-of-date photographs of the New York skyline. But these left her unaffected. Maybe mother's whole life since Daddy divorced her was what was called "vicarious": she felt what happened to others as if they were happening to her.

But it was different for Brian Hansen. It was all real for him — explosives and terrorists and the death of people you loved. He had lost his daughter, for God's sake. He'd had to go to Scotland and claim what was left of her body, and fly home with the remains of a woman too young dead, stone cold in the baggage compartment under his feet.

*

He didn't come to her high school graduation — not that she'd really expected he would, not after that weird discussion by the pool. She'd hung on to her last commencement ticket until the day before baccalaureate, and then she gave it to Fat Alan, who seemed genuinely surprised to have it.

When another whole week passed with no sign of Hansen at EcoMart, Cinda imagined he might have taken a job with the Homeland Security people — screening baggage, or taking fingerprints, or just looking for terrorists and in-general evil. She wondered if he would always be thinking about the daughter who'd been blown up over Scotland, and whether he used to imagine he might someday come face to face with the actual man who'd made the bomb or packed it into the suitcase, or who'd worn the stolen badge of a TWA baggage handler and loaded it onto the plane. And then what? Was that why he'd gone to work as a secret agent in the first place? She didn't know; she couldn't put herself in his shoes.

It was a shame nothing had happened between him and her mother — not that Cinda saw herself as a matchmaker, like one or another of Mother's friends who came around after the divorce and pushed her into the path of some middle-aged man smelling of cigarettes and aftershave. "Listerine breath," her mother would report, "and too many hands." Still, Brian Hansen had seemed a cut above — smart and reserved, and obviously a lonely person. One drawback was that Ruby, if she'd lived, would be almost Mother's age. Another was the possibility of a Mrs. Hansen, assumed to be divorced, but never once mentioned at poolside.

On her last day at EcoMart, Cinda decided to find out the range of the hand scanner she had used for almost a year. It was nearly three months since Hansen had vanished, apparently for good, and though she sometimes expected him to reappear in her checkout lane — more wish than expectation, she admitted to herself — he never did. Now that she was packed for college and ready for Mother to drive her to Savannah, it was likely she would never see him again, but the very first question he asked had stayed with her.

The experiment was a bust. After the last customer had left, and the front doors were locked, she aimed the gun at the magazine display across the aisle — a distance she estimated to be a little more than four feet. Nothing happened; she couldn't even see the thin line of the laser against any product code: not the TV Guide's, not the crossword puzzle booklet's, not even the National Enquirer's. When she leaned out over her counter to cut the distance in half, she thought she saw a red flickering over the Enquirer's UPC, but the scanner didn't register it.

"What are you doing?" Ronnie said. She had come out of the cash-up room, and now she was standing behind Cinda.

"Trying to find the range," Cinda said. "How far away can this thing scan?"

Ronnie laughed. "Eleven inches," she said. "Less than a foot. All you had to do was read the manual in the supervisor's office. You can ask Dolby. 'From two to eleven inches.' I'm quoting."

"That's not very far," Cinda said.

"It's enough. What were you going to do? Play Star Wars with it?"

Which, if the truth were known, wasn't so far off from what Cinda had in mind — not wars, exactly, but competitions among the cashiers. She'd thought they might set up different products at various distances, the more expensive ones farthest away and the cheap ones closer in. Everybody takes a turn, a certain number of scans, and high total wins. At game's end you could clear the register and the supervisor would be none the wiser.

"Don't be silly," Cinda said.

Waiting for her ride home, she amused herself by imagining that when she and her mother went through security on their holiday trip to London, Brian Hansen would be the agent at the checkpoint; then she could tell him about the game, and why it failed. He'd pass the metal-detecting wand up and down and around her, looking for keys and belt buckles and the coins that concerned him so much, and she'd say to him, "What do you suppose is the range of one of those things? How far away can you stand before you can't read me anymore?"

Original art courtesy Rob Grom.